Thomas J. Barrack, Jr. is an expert at taking risk. Whether he’s buying troubled banks in Asia, purchasing billions of dollars of distressed debt in the United States and Europe, buying U.S. banks in the midst of the financial meltdown, acquiring Miramax or Lodgenet in the entertainment business, buying PSG soccer team in France, or barreling through the salty spray of the rolling surf toward a Malibu beach, Barrack is a person who feels most alive in the midst of a treacherous swell, or amid the chaos of fear and uncertainty. Whichever it is, he adapts instinctively and confronts the challenge one incredibly prepared baby step at a time.

The 65-year-old founder, chairman, and CEO of Colony Capital in Santa Monica is the veteran champion who remains an All-Star playmaker.

An avid surfer, Barrack analogizes life in many aspects to surfing. In order to ride a big wave well one has to be mentally, physically, and spiritually prepared and choosing the right wave in the midst of a frenzied crowd overcome by adrenaline and sometimes inexperience is the test. “There are many great surfers who have god given talent,” he says. “I was not one of them. However, I learned that skill as a learned trait can make up for talent and that is a key to life. Many people have more talent in all of the arenas in which I compete; however, very few of them can outwork me or outlast me.”

A self-made billionaire over his 40-plus-year career, Barrack founded Colony Capital, a private equity real estate company, in 1991. Since then, the company has expanded its offices to 12 cities, nine countries and holds approximately $34 billion in assets, including $18 billion in 16 commercial real estate and distressed debt-focused funds. Barrack is as comfortable in the royal maglises of the Middle East, the Palaces of Europe or the Keiretsus of Asia as he is at home. He has also received the rare designation of the Legion de Honor from French President Nicolas Sarkozy. Friends and associates view him as a gifted specialist in the art of a “Cultural Sixth Sense” and he certainly spends as much time in the air as on the ground. Given this level of achievement, the man could easily be the aloof cliché. He is, delightfully, anything but that.

“Many people have more talent in all of the arenas in which I compete; however, very few of them can outwork me or outlast me.”

Barrack has a dynamic humility about him that is commanding and disarming, born out of his history. “I can tell you, I am still a grocer’s son,” he says. “My competitive advantage is that I am still my dad’s son. I am constantly scouring the globe to find oranges that are ripe to be picked in one part of the world and sold in another part of the world that is hungering for oranges.”

The “edge” is that proverbial chip on the shoulder that supposedly motivates people to become great. It is discussed constantly in athletic circles: The football champion with three Super Bowl wins, who still resents that he was overlooked for six rounds before being drafted as a lowly backup quarterback; the basketball wunderkind whose championships people say hold less worth because at the time he wasn’t the team’s most dominant player.

Barrack’s competitive advantage eluded him for many years. As the son of a grocer whose grandparents emigrated from Lebanon, Barrack always felt slightly out of step with his “pedigreed” classmates. During his teen years at Loyola High School as well as his college and law school years at the University of Southern California, he often found himself in awe, eyeing others’ attributes. “I was never the smartest guy at anything nor the most naturally talented at anything,” Barrack recalls. “I worked harder, tried harder and did not mind taking risks at all.”

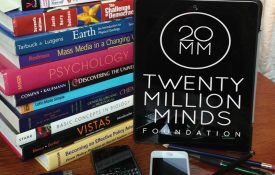

Thomas Barrack, Jr. at his beloved “Piocho Rancho” in Santa Ynez, CA, home to Happy Canyon Vineyard

Barrack was hired out of law school by the firm of Herbert W. Kalmbach, President Nixon’s personal lawyer. He earned a little more than $9,500 that year, which wasn’t bad in the early 1970s. He logged hours he knew would impress the partners, and 5 a.m. Saturday mornings became a regular practice.

One morning serendipity stepped in and made Barrack an offer – his first taste of risk. It was his second month at the firm and on this Saturday morning the firm’s senior partner came in, saw Barrack and asked him, “‘Aren’t you Lebanese or something like that?’ At that time they thought it was a sexual preference,” Barrack recalls with a laugh. It was 1974. The firm was negotiating a gas liquefaction contract and needed a representative to travel to Saudi Arabia. “Do you know anything about that [gas liquefaction]?” he asked Barrack. “I said, ‘It’s funny you should ask that because I happen to be a gas liquefaction expert.’ Of course I didn’t even know what gas liquefaction was.”

Barrack’s excitement about this opportunity was not matched by his mother. Decades before, his grandparents fled Lebanon for the United States. When he told his mom he was headed back to the Middle East and Saudi Arabia, an area with centuries of political and religious warfare, “she broke into tears,” Barrack says. My family, like all great American Immigrant families had left behind the trauma and frustration of the Old Country to build a new life in America for themselves and their kids. I graduate from USC, I go into law, she is so elated, and 60 days later I said, ‘and by the way, I’m going back to our homeland.’”

So, the firm flew Barrack to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, one of the most primitively distinct places he remembers seeing at the time. Eventually he arrived at Dhahran, which was the headquarters of a Saudi Arabian subsidiary of Arabian American Oil Company (ARAMCO). In Dhahran, Barrack was a project finance lawyer negotiating between ARAMCO, Fluor and its associates, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia – in three languages. Conditions were primitive and few Westerners were in the Kingdom at that time. He was 24 years old. His pedigreed friends and fellow class mates were at home in New York and Los Angeles living a much different life.

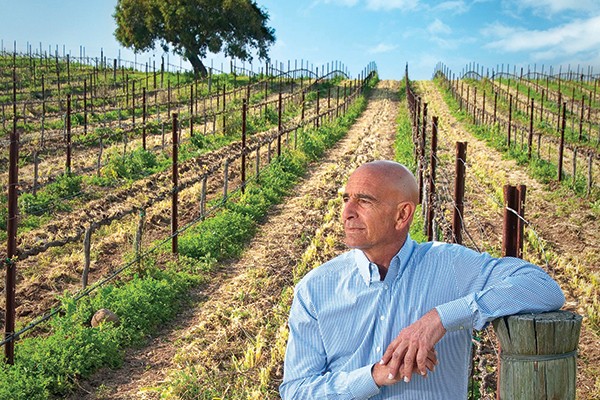

Barrack, Jr. with Prime Minister Mikati of Lebanon (left) and Rob Lowe (center)

One of Barrack’s many attributes is his ability to tell a story and that is befitting of a man who is still living a storied life that has the detail of a world almanac and biographical memoir in one. “True story,” Barrack says, shifting in his seat, a mischievous curl at the edge of his lips that leads to the sparkle in his eyes. You do not want to miss a word and you lean in.

“I’m sitting in as a young finance lawyer within a camp of ARAMCO. ARAMCO had massive compounds [Dhahran camp was the first company compound founded in the late 1930s and can house 11,000 people] and the compound provided us with the only things you could do there. The guy who ran the project upon which I was working came and asked me if I play squash. I said, yes. And so he said, I have someone I want you to play squash with this afternoon. That afternoon I meet a nice Saudi kid. He introduces himself and we play. Well, when we’re done he says, ‘This is great. Do you want to play tomorrow?’ I said yes. It ends up that he was one of the sons of the king. And, after about three weeks he tells my boss he wants me to work for him. Why? Was I the most brilliant? For sure not. Was I the most capable? For sure not. But I could play squash and he and I became pals,” says Barrack with a grin.

So Barrack quit working for the Kalmbach firm and started working for a couple of the young Saudis. Over that year the squash duo grew to include other princes and sons of very influential Saudi men. Toward the end of 1974, Barrack received a call from the senior partner at Kalmbach. They had a client, investor Lonnie Dunn, whose trans-shipment terminal for oil was stalled on the island of Haiti. OPEC had just been formed and the only way for the transshipment terminal to go forward was if Haiti signed a favored-nations contract with Saudi Arabia. So the firm called Barrack for help.

“This was serendipity. I knew nothing about real estate. I was a finance guy … I started looking at life like I do riding a wave. Choose the one you may never have an opportunity to see again.”

Dunn flew Barrack and the group of influential Saudi sons to Haiti where they spent three weeks enjoying the island before sitting with the nation’s infamous leader Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier. Barrack knew enough Arabic and French to serve as a translator, but while the “boys” talked to Duvalier about developing diplomatic relations, the Haitian leader’s eyes were transfixed on one of the Saudi prince’s diamond-studded watch. Seeing this, the prince offered his watch to Duvalier, who took it and then a few minutes later abruptly stopped the meeting and left.

“My whole life went before me,” says Barrack, who thought that because he was not only the connection, but also the translator between the Saudi contingent, Dunn, the law firm and now Duvalier, that he would be blamed for the deal falling through. “I thought, ‘I’m dead,’” he says. “And even worse, Baby Doc has now taken the watch and he wasn’t handing the watch back!”

Duvalier did eventually sign the deal and Dunn successfully sold the transshipment terminal with the Saudi contingents help. As thanks, Dunn offered Barrack the job of running his real estate empire back in America. “This was serendipity. I knew nothing about real estate. I was a finance guy,” Barrack says. But he chose to jump at the opportunity to work for Dunn in spite of the risk and, “I started looking at life like I do riding a wave. Choose the one you may never have an opportunity to see again.”

Over the next six years, Barrack built Dunn’s business to the point that in 1980 its real estate holdings included 3 million square feet of office space in six states. But Dunn was spending money, “faster than I could make it,” and Barrack was ulcerating from the stress. He convinced Dunn to sell and the buyer was G. Donald Love, chairman of Canadian-based Oxford Properties Group, Inc. Love, an entrepreneur and self-made multi-millionaire, took a liking to Barrack and bought Dunn’s business under the condition that Barrack ran the U.S. portion. Barrack did, and in the mid-1980s sold the business and then served as Deputy Undersecretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior under James G. Watt in the Reagan administration.

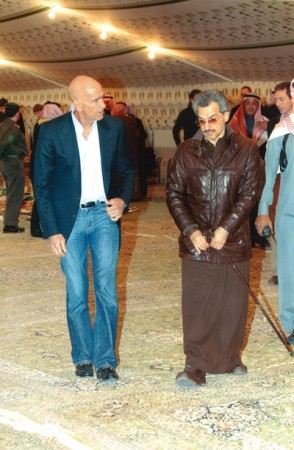

Barrack, Jr. with His Royal Highness Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Alsaud

Following his service for the Reagan administration, Barrack joined E.F. Hutton & Company in New York and ran Real Estate Investment Banking for then-Chairman Robert Fomon before joining the Robert M. Bass group in 1984. At the Bass group, he learned the building blocks of what has become Colony Capital. “I would not be where I am today if it were not for Robert M. Bass,” acknowledges Barrack. “He built and designed the team and coached us on how to move the ball down the field.”

“Colony’s investment theme, the way we’re organized, the way we analyze, the ethical and moral tombstones we abide by are just a transition of what I learned at Bass,” says Barrack. “We never focused on the real estate business as normal people do, such as building, constructing, and selling. It was finding that inefficiency in operating companies that are real estate rich.”

In 1990 the U.S. Government formed the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC), charged with liquidating, primarily mortgage loans deemed insolvent as a consequence of the S&L crisis. Between 1989 and the mid-1990s the RTC sold 747 thrifts with total assets of $394 billion, according to the FDIC. Seeing how he could utilize the RTC, Barrack took the troubled mortgages he had been charged to fix, along with the knowledge he had gained at Bass alongside legendary investor David Bonderman who was his then boss, and launched Colony Capital in 1991. His investors included Bass, Bonderman, Eli Broad, Cargil, two Middle Eastern and Asian families, and GE Capital.

“And that was the onset of Colony – starting in distress,” says Barrack. “We became the largest acquirers of RTC assets, distressed assets, from 1990 to 1994.” After his domestic success with distressed assets, Barrack, like a surfer from Endless Summer followed recession waves around the world.

“Then Europe went in the tank and we took there that same set of principles, rules, and disciplines launching our European headquarters in Paris,” he explains. “Then in 1997 the Asian contagion hit and we did the same thing and saw another opportunity. We bought interests in banks in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan.”

Barrack, Jr. going head to head with Adolfo Cambiaso – currently ranked #1 in the world

By 2007 Colony Capital could claim a “15-year run of only upward-level adjustment on all assets, proliferated in large part by plentiful, cheap, and available debt from banks,” says Barrack. When The Great Recession hit in 2008, Colony took a few hits like all other private equity firms. Barrack was perfectly positioned to ride that financial wave. While most everyone scrambled to switch their investment strategy and banks hoarded the stimulus funds, Colony Capital purchased $14 billion of debt in nearly 18 months, according to Barrack.

Currently, Colony is purchasing as many single-family foreclosed homes as it possibly can from trustee sales and the Multiple Listing Service. The firm currently owns 10,000 single-family homes. After a home is purchased it is retrofitted, rehabbed, and rented. “The benefits to all involved in this program are amazing,” enthuses Barrack. “The single-family, residential mortgage business is the single largest asset class in the world—120 million housing units and it’s between $6 trillion and $12 trillion in value,” he says.

Barrack’s investments regularly come under scrutiny, as did Colony’s purchase of Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch and his purchase of Miramax’s library of films. “We gave our investors their money back in 10 months because content is so hugely in demand,” he says. Barrack is also rumored to be in the mix to purchase Anschutz Entertainment Group.

Controversy and criticism, however, are of no concern to Barrack. Like a 17-year NBA veteran who still blows past defenders with ease, or a 40-year-old surf champion who still manages to turn the best waves and sit atop the surfing world, Barrack is not slowing down but is searching for his next risk to conquer.

“In order to accomplish extraordinary things and deliver extraordinary returns you have to take extraordinary risk,” he states. “Otherwise all returns regress to the ordinary. My job is to push my people, associates, and partners through their own comfort barriers and shatter their fear by providing them a safe harness of knowledge, wisdom, and instinct as they get to that edge. Fear is normal and healthy, but panic and miscalculation is a result of not practicing how to harness and control fear before you get to the edge.”

Barrack shares a conversation he had with his good friend, surfing legend Laird Hamilton. “I asked him, ‘How could you not be terrified at the moment you are paddling into a 60-foot wave knowing that any miscalculation will be your doom?’ He looked at me and said, ‘Because I was terrified for thirty years, getting ready for that moment.’”