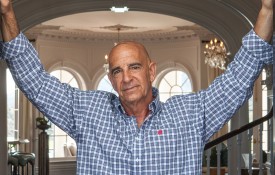

As past president of Columbia Records, founder of Arista Records and J Records, and chairman of RCA Music Group, Davis could open his own Rock and Roll Hall of Fame based solely on the artists he has discovered and/or signed. Still at it as chief creative officer of Sony Music Entertainment, Davis has an office on the top floor of the Sony building in New York City. When he travels to LA (every six weeks or so), The Beverly Hills Hotel is his home base.

A shade early for our afternoon appointment, the CSQ contingent gathered in the main lobby and when it was time, wound our way through a sun-drenched pathway leading to the bungalow that Davis has occupied for years – the same bungalow where he sat with Whitney Houston to select the songs that would comprise her debut album three decades earlier.

Answering the door resplendently attired in a dark blue sweater with white trim and a dark blue shirt with a coordinating blue-and-white striped tie was our host, Mr. Clive Davis. Eyeing us, he smiled and graciously welcomed us in, wryly remarking that Katie Couric hadn’t brought this many people when she’d interviewed him a few weeks earlier. At the time of our interview, Davis was in the throes of promoting his memoir, “The Soundtrack of My Life,” released in February (see “Required Reading,” p. 98).

Clive Davis with Whitney Houston, celebrating her seven straight #1 singles

On the glass coffee table in the living room was an assortment of demos, lyric sheets, and notes outlining current projects being pitched for Jennifer Hudson, Aretha Franklin, and others. Davis isn’t one to take the weekend off, and keeping his work at arm’s reach seems to be a natural state for him, especially as he revealed he does not listen to music unless he’s working.

Seated facing each other “summitstyle” in two comfortable, high-backed chairs alongside an ornate accent table and interior décor plants, we covered mentors and early influences in his life, how the industry has changed throughout his various positions of influence, his infamous pre-Grammy parties, and the dense array of superstar artists whose careers he either launched or positively affected in some way. He also told a great Janis Joplin story.

Davis is never at a loss in recalling a name, from artists to bands to the industry peers for whom he has special respect. His memory is sharp, his words are thoughtful, and his manner is animated. At various times, he claps his hands or snaps his fingers for emphasis.

He grew up in Brooklyn, New York. The youngest male child of a lower middleclass Jewish family, Davis’s father Joe was an electrician and later a traveling tie salesman with the knack for making friends. His mother Flo worked in a women’s clothing store as a saleslady to help out with money at home. Although never poor, they struggled to make ends meet.

Davis discovered early on that he was academically inclined. He loved public speaking and became a straight-A student at Erasmus Hall High School, earning a full-tuition scholarship to New York University. During his freshman year, his parents died. To this day, Davis credits his mother as “the best advice giver in my life.” Davis eventually graduated magna cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa and was offered a full-tuition scholarship to Harvard Law School. He was on his way to becoming a lawyer without the slightest interest in music beyond casual listening and a fondness for Broadway musicals.

Clive Davis with Aretha Franklin

His first position at Columbia Records stemmed from an offer by chief counsel Harvey Schein to teach Davis everything about how Columbia’s department works and if things worked out with Schein becoming head of International within a year, he would appoint Davis chief lawyer for Columbia Records. Davis accepted the job offer, and a serendipitous series of events would follow.

Four years later, group president Goddard Lieberson and CBS founder William Paley embarked on an ambitious reorganization, diversification, and acquisition program that resulted in Lieberson giving Davis Columbia Records to run, albeit with an odd title of administrative vice president. The importance of the new role was he would oversee all of Columbia Records operations, including A&R (artists & repertoire), which is the driving engine of any record label. In 1967, Davis was appointed president of the label. He was 35.

By 1970, Davis had signed new artists to Columbia and its sister label Epic, including Donovan, Janis Joplin, Carlos Santana, Johnny Winter, Blood, Sweat & Tears, Chicago, and Laura Nyro. He also renegotiated the expiring recording agreements of Andy Williams, Barbra Streisand, Bob Dylan, and Simon and Garfunkel. From 1967 to 1970, Columbia’s market share grew from 12 to 22 percent and it comprised an increasingly larger portion of parent company CBS’s bottom line.

In 1973, Davis was unceremoniously ousted from Columbia and charged with expense account violations. After a baseless, sensational media smear campaign, Davis was eventually exonerated from any wrongdoing. Barely missing a beat, he founded Arista Records a year later, acquiring artists such as Barry Manilow, Melissa Manchester, and Dionne Warwick. He signed Whitney Houston in 1983. She would eventually sell over 55 million units in the U.S. alone.

“The most gratifying experience was to see as many as twenty of the top executives at Arista agree to come with J Records, making it possible to start as a formidable instant major.”

In 2000, Davis launched J Records. The following year he released Alicia Keys’ debut CD “Songs in A Minor,” which has sold over 12 million copies worldwide. Both record labels did so well they were absorbed by RCA Music Group in 2002, making Davis president and CEO. He remained there until 2008 when he accepted the position of chief creative officer of Sony Music Entertainment, where he would again have day-to-day responsibility of working with and producing artists that he loved.

Clive Davis with Bruce Springsteen

“I think the most meaningful professional experience was [when] Bertelsmann – which had a controlling interest in Arista Records – had imposed its rule for its corporate executives that once you had turned 60 you had to move into some chairmanship or outside consultancy and in effect [leave] the operational level,” recalls Davis. “I did not want that for my career, so they had to make an unprecedented offer, because they did not want to lose me. They gave me $150 million and ten artists to start a new record company, which became J Records. The most gratifying experience was to see as many as twenty of the top executives at Arista agree to come with J Records, making it possible to start as a formidable instant major.”

The octogenarian mogul still keeps an active work schedule, and he’s not one to turn in early. “I go to bed at 2:30 in the morning,” he announces, working backwards. “I leave the office and do dinner for two hours every night between 8 and 8:30 and get home between 10:30 and 11. Then I do reading until 12 or 12:30.” If the Yankees played that night, Davis will watch it on his TiVo. He always watches 60 Minutes and keeps current on American Idol and The Voice.

“I pair people that you’ll never see on stage. They began to copy that at the Grammys.”

Davis considers himself lucky if he gets six hours of sleep in a night. “I wake up at about 8 a.m.,” he continues. “These years I get to the office at 11. I don’t do lunch…. On the weekends, I bring home records that make the charts to keep my ears current.”

His office, on the 35th floor of the Sony Entertainment building, offers an aweinspiring, panoramic view of the city. But the view on the inside isn’t bad, either. “I am very grateful that my office is magnificent,” he says in earnest. “I spend so much time there. The walls are filled with pictures, so I’m surrounded by wonderful memories.”

Some of his fondest memories relate to his annual pre-Grammy party, a tradition that started in 1975. That year, Barry Manilow’s song “Mandy” was nominated for two Grammys. “It was a combination of welcoming Arista to the industry because it was our first year of operation and we were celebrating our Grammy nominations, Davis says. “When Elton John, Stevie Wonder, and John Denver came I knew I was on to a very good thing. We did it [the night] after the Grammys the first time. Then I switched it to the day before the night of the Grammys, which continues to this day.”

Clive Davis receiving his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

Davis takes great pride in his annual pre-Grammy parties, arranging all the artist performances and eclectic stagings. “I pair people that you’ll never see on stage,” he states. “They began to copy that at the Grammys. I’m talking about when I paired the young Alicia Keys and Aretha Franklin, because it was always Alicia’s dream to perform with the great Aretha. Or, Lou Reed dueting with Rod Stewart.” It’s all about creating a memorable evening of legendary performances and some unexpected surprises. Two years ago, Davis decided to bring out three guests before the music started, just to mix it up and keep things fresh. “I introduced Paul McCartney, Sly of the Family Stone, and then Prince.” The electricity in the air was palpable. “This is a seated dinner with name places coded by table,” Davis points out. “No one had seen them at the cocktail hour.” Another surprise guest the past two years has been Joni Mitchell. “She is so reclusive, but she loves this night.”

In terms of industry peers, Davis holds longtime Columbia Records president Goddard Lieberson in high esteem as well as Atlantic Records founder and president Ahmet Ertegun. “[Their] personalities survived corporatization,” he notes. “They were not absorbed or evened out as so many executives are. Mo Ostin certainly had a tremendous track record as head of Warner Bros. Records, no question.” Davis mentions Joe Smith, Neshui Ertegun, Doug Morris, Jimmy Iovine, Berry Gordy, Jac Holzman, Seymour Stein, and Clive Calder as well. “I have great respect for what Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss built at A&M,” adds Davis. And he’s just getting started. He goes on to mention Terry Ellis and Chris Wright at Chrysalis, Richard Branson at Virgin, Chris Blackwell at Island, Tommy Mottola and Donnie Ienner at Columbia, Bruce Lundvall, Russell Simmons, Lyor Cohen, and L.A. Reid.

David Geffen, in particular, impresses Davis. “In the accumulations of wealth he outstripped all of us,” Davis admits, adding, “He was a brilliant manager. He did incredibly well in the formation of Asylum and then Geffen Records. He had a wholly different style and was uniquely creative.”

Speaking of style, Davis has plenty of it. Rivaling his taste in music is his taste in fine threads. Early on, he made a conscious decision to separate himself visually from the creative element he was representing. “The important lesson that I learned in general is that artists don’t want you to be one of them. It may work for the first few years if you are a carouser or a druggie, whether you’re a manager or an agent or a record company head,” he observes.

“Ultimately, [artists] want security,” Davis says. “If they are prone to the fast lane they tend to look for those managers or those people that they want to protect them, and not to emulate them. The idea of changing your style, I don’t think ever works. So, I’m not walking around in jeans over the years to show how hip and contemporary I am. Some might. I was, however, influenced by Goddard Lieberson. I always imagined that he had panache and style. I love what he did years ago in matching his English shirts with a handkerchief, because most people don’t match. If they match at all, they match the tie.”

Clive Davis with Janis Joplin

In terms of image and public perception, Davis feels the music industry as a whole has been mischaracterized for decades. “When you read about the industry – and I’m not saying that some parts of what is said are not accurate – but what is said doesn’t characterize the whole industry as I’ve known it in my lifetime,” Davis explains. “The senior partner at my former law firm once said to me, ‘You’re not going to fit into [the music] industry.'”

But Davis saw it differently. “The picture of the gold-chained Zoot Suiter with fingers snapping that you read about does not characterize the people in the industry. If you [consider the people] that we have talked about [Ostin, Ertegun, Gordy, Morris, Alpert & Moss et al.], these are men of quality executive stature. They have been the creative architects of the entire industry. They don’t fit this kind of [easy-to-mock] stereotypical character.”

As our time winds down, the phone rings. Davis is due at a wedding in Beverly Hills at 4:30, and that’s his cue to wrap things up and get ready. “I’m currently in the throes of getting incredible letters, maybe 20 a day, [reacting] to “The Soundtrack of My Life” from people from all over the world,” he says. “It’s been unbelievably exciting.” The book entered the New York Times bestseller list at No. 2 this spring and stayed in the Top 10 for nearly three months.

And what does Clive read? “I’m a magazine reader,” he professes to the silent delight of this writer. “I used to like reading Daily Variety. I’m disappointed at its absence. But, I read Rolling Stone, every issue, I read Vanity Fair, every issue. I read People magazine, every issue, TIME magazine, every issue. I read The New York Times every day and the Post.”

The lifetime subscription to CSQ is on its way, Clive.