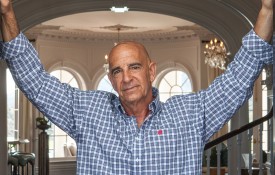

It’s less than a week since he consummated his latest and most publicly visible transaction — acquiring a professional basketball franchise — but Tom Gores still makes a point to apologize for the extent to which his availability for an interview has been at a premium. “Things got a little crazy last week with [finalizing] the deal,” he says, referring to his purchase of the NBA’s Detroit Pistons, the terms of which became official on June 1. “Thanks for being patient.”

The Pistons represent only a small portion of Gores’ investment empire. The genial and driven 46-year-old business mogul is chairman and CEO of Platinum Equity, a global private equity firm whose holdings include 35 operating companies in a vast array of industries including manufacturing and industrials, automotive parts and supplies, telecommunications and technology, paper and packaging, transportation, print newspapers, and, now, a professional sports franchise. He is by desire and by design a man in perpetual motion.

As such, a Monday night conference call from his Beverly Hills office fits right into Gores’ (and CSQ’s) necessarily flexible schedule. It’s apparent within a few moments that he is dialed in and focused on the matter at hand, fully engaged and giving gracious attention to the writer and publisher of a regional magazine three time zones removed from the site of his latest coup.

As such, a Monday night conference call from his Beverly Hills office fits right into Gores’ (and CSQ’s) necessarily flexible schedule. It’s apparent within a few moments that he is dialed in and focused on the matter at hand, fully engaged and giving gracious attention to the writer and publisher of a regional magazine three time zones removed from the site of his latest coup.

“The reception and excitement has been incredible,” he says of local reaction to the deal, which also includes Pistons’ home arena The Palace of Auburn Hills and the DTE Energy Music Theatre (formerly known as Pine Knob). Still, he is realistic in assessing the task at hand. “We’re going to have to go to work,” he affirms, acknowledging the Motor City’s blue-collar work ethic and the intense pride with which fans follow the fortunes of their beloved sports teams, before confidently adding: “We’re going to find a way to deliver — not just bring the Pistons back, but help Michigan get back on track, too.”

Gores has the luxury of the off-season to conduct the hiring process for a new coach, as well as the proven basketball acumen of team president and former Piston great Joe Dumars to consult with. The new owner is clear on one criterion: The new coach must mesh with the local culture.

If anyone is qualified to speak to the sensibilities of the Michigan mindset, it is Tom Gores. Years before he evolved into the dapper L.A. dealmaker whose financial empire includes over 35 portfolio companies — putting his personal net worth at roughly $2.4 billion — he was just a small-town Midwest kid. Born in Israel to a Greek father and a Lebanese mother, his family emigrated to the United States and settled in Genesee, ten miles outside of Flint, when he was still a toddler. He played baseball, football, and basketball in high school and went on to earn a degree in construction management from Michigan State University, where he met his future wife, Holly. After they had been dating for nine months, he told her he wanted to pursue promising career opportunities on the West Coast. “I asked her to go,” he recalls, “but I didn’t think she’d say yes.” She accepted his offer, and together they piled into his black Cadillac and embarked on a cross-country journey that would seal their future as a couple. The year, ironically, was 1989, and the Pistons’ fabled Bad Boys (Isiah Thomas, Bill Laimbeer, Dumars, and company) had just steamrolled over the mighty Lakers in the NBA Finals. The stage was set for another Michigan-grown product to take L.A. by storm.

Gores immersed himself in acquisitions, joining eldest brother Alec, who founded The Gores Group in 1987. Within a few years, Tom was ready to step out on his own. He founded Platinum Equity, a private equity investment firm, in 1995. “I didn’t approach anyone for capital [to start the business],” he recalls. “I just thought if I could find one deal that made sense, I’d take it from there. I had a couple hundred thousand bucks, but I had debt, so I was in a negative position.” Sheer determination paired with a well-conceived strategy was a compelling success factor. “I decided to figure out how to get it done,” he says simply. “I loved the corporate divestiture market, because you could find companies within these big divisions that maybe weren’t being taken care of,” he explains. “I figured if I could find one or two of those, I could make a living.”

What Tom Gores modestly refers to as “a living” would translate into “a killing” in virtually every other corner of the universe. Through Platinum Equity, Gores estimates he has made over 120 acquisitions. Ranked 31st on Forbes magazine’s 2010 list of largest privately held companies in the United States, Platinum and its operating companies employs 40,000 people worldwide with diversified holdings representing avast array of industries, from media and communications to industrial and manufacturing.

Alec Gores continues to reap success with The Gores Group, which has grown his net worth to $1.7 billion. A third brother, Sam, has also thrived on the West Coast, albeit in a more conventional L.A. industry: entertainment. In 1992, he formed Paradigm Talent Agency, whose roster of talent includes The Black Eyed Peas and Philip Seymour Hoffman, among others. Tom and Sam’s respective offices are separated by courtyard that features an ornate fountain, a stunning visual landmark of Platinum Equity’s world headquarters on North Crescent Drive in Beverly Hills.

One unique aspect of Platinum’s headquarters that speaks to Gores’ personal style is a plush lounge located adjacent to his office, where some of his biggest deals are sealed. This Club Room provides the convenience and comfort factors, both important aspects of doing business. Gores reasons that having a place to hang, enjoy a cigar, a drink, or sit down to dinner spontaneously — rather than leaving to meet up elsewhere — is efficient and his preferred way of closing a deal. “I’m much better at a deal when I’m hanging,” Gores says, which suggests he feels that doing business can be an aesthetically comfortable experience.

Gores’ philosophy on empowering people to achieve their goals at work and at play is a natural fit for the world of competitive sports. “Part of it is showing the leadership that you believe in the values… [the] hard work, practicing, executing…. We’re believers in doing the basic things and the results will come.” His conversation is peppered with the ideals that comprise the cornerstones of his success — preparation, flexibility, and risk-taking — and he delineates how putting them into practice can lead to great things. The spirit with which he shares his philosophy is contagious. It’s no surprise then to learn that this passion spills over into a consuming recreational pastime, coaching kids’ soccer.

Being able to accept loss and turn the page is a character-building process, and it’s clear that his experiences in his youth shaped him as an adult. “My mom was a great inspiration,” he recalls. “Whenever I did fail or lose a game, she made sure I got back on my feet. She never killed my spirit.” Providing instruction to the bundle of unbridled energy of the typical preteen requires not so much a different skill set, but a different application of the same tools that serve Gores so well in the boardroom. “With coaching kids, a lot of times it’s about making sure you don’t take the motivation out of them,” he points out.

“I understand if I’m the CEO I’ll do my job, but I’ll never confuse that with humanity,” he says. “If I’m in a conference room and I need to lead a meeting, I’ll do it. In the meantime, if I’m in the regular world, I’m a regular guy.” Gores began coaching six years ago when his eldest daughter took up the sport. He and his wife have three children, ages 14, 13, and 9. He works to instill in them the same values he learned through sports. “It’s one thing to have the talent,” points out Gores. “It’s another to have the hard work ethic.”

Call it a nature vs. nurture equation if you’d like, but whatever it is, Gores has found a solid balance between the two. And he is vigilant in maintaining it. “I told someone the other day, ‘The day I think I’m a better businessman than a father is the day I don’t respect myself,’” he reveals. Gores points out that most aspects of life and business is a series of choices, but being a parent involves a more comprehensive set of rules. “If you’ve got something important to do for your kid or your family, figure out how to get there,” he says. “We drive that [point] home [at Platinum]. If you’re successful in business, but you sit around in your office having the thought that you’re not being the best dad, then it’s not complete.”

“I have a natural love for people and want them to be their best,” says Gores, and his immediate staff bears testament to this. Through encouraging, challenging, delegating, and leading by example, Gores has built a highly capable workforce whose loyalty is illustrated by the fact that the senior management team’s average tenure is 11 years.

Charlie Ittner has been employed at Platinum for seven years. He knows firsthand of Gores’ propensity to allow employees to expand their skill set through taking on new experiences. “I was hired as a runner,” he told me in a brief conversation we had while finalizing the interview with his boss. “Over the years, he continued to give me responsibilities that outsized my experience. Tom establishes bonds with people who work for him,” said Ittner, who now handles the task of managing Gores’ demanding schedule and full agenda, serving as Director, Office of the Chairman. “This is a place that allows you to grow.”

Gores’ determination to bring his winning ways to Detroit is hard to refute. Through the years, he maintained a strong connection to his roots, saying, “As a young boy, when things inspire you, you remember it.” Becoming the owner of a team he cheered for in his youth is especially gratifying, but this is not his first foray into the pothole-riddled playing field that has distinguished the Michigan economy ever since filmmaker Michael Moore’s Roger and Me chronicled the downfall of the city of Flint due to auto giant General Motors’ massive downsizing of its workforce in the 1980s.

Platinum Equity is not afraid to cut costs through downsizing. The film specializes in stabilizing under-performing businesses that often come with unsustainable cost structures. But Gores and his cohorts at Platinum take great pride in their ability to come out of those restructuring situations with healthy companies that are well-positioned to grow revenue and add jobs.

The firm has executed this strategy successfully and contributed to the economic vitality of communities across North America and Europe. In Chicago, for example, Platinum Equity owns the city’s oldest continuously operating company, Ryerson, Inc., a steel distribution business founded in 1842. In San Diego, Platinum owns the city’s largest daily newspaper, the Union-Tribune, founded in 1868 (Union) and 1895 (Tribune). In Jeffersonville, Ind., and dozens of cities between the Gulf of Mexico and Lake Michigan, Platinum owns American Commercial Lines, a shipbuilding and marine transportation business founded in 1915 that operates more than 2,500 barges and boats delivering goods along the U.S. Inland Waterway System, which comprises the Mississippi, Arkansas, Ohio, Tennessee, Cumberland, Allegheny, and Monongahela rivers, among others.

Despite his firm’s global reach, Gores understands that the Pistons acquisition, along with his own roots in Michigan, will draw particular attention to Platinum’s investments in that state, whose troubled economy may be showing signs of life but still could use a lift. “We’ve done a pretty good job getting ourselves set up in Detroit,” says Gores, who just closed a deal with Belleville-based Active Aero, which specializes in expedited freight solutions, the previous week. That brings the total to five Michigan-based businesses he now owns. “We want to add jobs [to the state’s economy], so we’ll continue to look [for acquisitions] where it makes sense,” says Gores, who estimates his employees for his Michigan holdings at well over a thousand.

As the deal for the Pistons was in the final stages, Gores remembers, “Somebody told me we can’t afford to make mistakes.” His response? “We’re going to make mistakes. We can’t afford to be afraid of mistakes. To the extent that they happen, we’re going to adjust. The thing you find in business — and it’ll be the same in basketball — is you can make a lot of the average decisions [turn out] pretty good if you’re able to inspire and correct and move things around.” Gores clearly has retained a close kinship with humility. “I’ve been wrong plenty of times,” he admits. “I’ve made the wrong call on a deal or bought the wrong business, and guess what? I’ve gotta adjust — the next day. Not sit in my decision for three months. Your ego’s out of it…. It’s the owner’s job to say, ‘Let’s make some mistakes, but let’s make some good ones.’”

“We’re going to shake it up [and] do things the state and the city can be proud of,” Gores predicts. “They know we’re astute business people and we must see something in the opportunity. In this case, the community is the customer,” he says, adding, “I think we’re going to do everything that we’ve done at Platinum in Detroit.” The city’s Motown roots are an important part of the city, and Gores, a self-professed music fan, intends to tap into all aspects of the rich local culture. Does that mean more halftime music performances at The Palace? “You’re on the right track,” he says without divulging specifics.

Not to short-change Mark Cuban’s brilliance in the business world, but most people don’t think of him as the guy who started MicroSolutions; he’s the fiery and charismatic owner of the NBA Champion Dallas Mavericks. How does Gores anticipate handling the public notoriety that comes with owning a professional sports team? Will it change him? Has it already started to? “I think when things get complicated, as long as you keep them simple, you’ll stay real,” he says. “That’s always been important to me, to not get caught up in the hoopla.”

For a man who built his fortune amidst the trappings of Hollywood, the unofficial hoopla capital of the world, Gores’ singular focus with getting results is unswayed. Still, he prefers he not be judged solely on his past successes. “I’ve always appreciated people who believed in my potential and not just my track record,” he says as we conclude our conversation. For all his accomplishments, perhaps the most impressive thing about this billionaire financier is the fact he still feels he has something to prove.