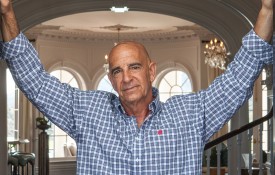

The Adaptive Reuse Ordinance, passed in 1999, facilitated the conversion of dozens of historic and under-utilized structures into new housing units. It is considered one of the most significant incentives related to historic preservation in Los Angeles. While he did not write the legislation, New York native Tom Gilmore is associated—more than anyone else in Los Angeles—with its successful implementation. Twenty-five years after he arrived in the city, Downtown is in the midst of a cultural and economic revitalization. Gilmore’s latest project, the Old Bank District Museum, an 80,000- square-foot arts center scheduled to open in 2017, will be the latest jewel in a neighborhood that he has resuscitated.

CSQ When you first arrived in LA, how did your vision for real estate come together with the Adaptive Reuse Ordinance?

TOM GILMORE The reality was that in the Old Bank District, the buildings I already had in escrow and was slowly closing on one at a time, at the time I was taking a pretty big gamble. The city was talking about the Adaptive Reuse Ordinance and moving on it to some extent, but I wasn’t entirely sure it was going to happen. I was a little bit out on limb, [and] had it not occurred, the process for transforming the commercial buildings into residential would have been a lot harder. … Once the city became aware that I was trying to move forward … they reached out to us and we became part of the process.

CSQ What have been some of most impactful changes you’ve seen in the city since you arrived 25 years ago?

TG With any great story, there’s a lot of bad before the good. After the riots and earthquake and after decades of Downtown becoming more decentralized and the City of LA basically abandoning [the area], it was ripe culturally, sociologically, economically, to finally rediscover itself. A couple things happened architecturally and development-wise that were pretty important and that we played a part in. There was the initiation of Staples [Center] and ultimately L.A. Live, there was the re-funding and re-imaging of Disney Hall; and on our side, this notion that a city center cannot sustain itself without a 24-hour population. It could not be a commuter based center; it would never survive.

CSQ Do you have a theory as to why DTLA went through a decline?

TG Transportation was ultimately the primary mode of tearing apart Downtown. Everything was done to facilitate the car. A good 25 percent of Downtown was demolished to create surface parking lots. Mass transit we had was eliminated and replaced by a mass-transit system based on the car. The other thing was, the wealthy founders of the city, the Chandler family, the Huntingtons, [and] the large stakeholders that once occupied Downtown moved to the suburbs in Pasadena and Pacific Palisades and so on. The civic culture of LA became marginalized and peripheral.

CSQ What areas of improvement would you like to see over the next 5 to 10 years?

TG You can’t do too much mass transit. They have to continually not lose focus on that and make sure mass transit reaches enough places so the system is a viable alternative to the automobile. Right now it is a very limited alternative, but it’s a good start. The plans are pretty expensive, so the city and county deserve credit for that. The city has come to conclusion that density is sustainable in certain areas like Downtown and Hollywood. They should promote that.

CSQ From your perspective, how does Downtown LA stack up with New York today?

TG In New York, everyone has a house in the country, but they live in the city, too. Here in LA, once people moved out of the city, they were never coming back. Interestingly enough, that is reversing. Some of those older family names [Chandler et al.], the second, third, and fourth-generation of those families are beginning to re-occupy Downtown, which I find fascinating and wonderful. And people like me, who develop here, choose to live here. I live on 4th and Main. I’ve adopted LA and it’s adopted me, and that’s that. I’m not going anywhere.