Rick Caruso sat with his wife, Tina, their four children, and the family’s pastor for Sunday dinner. It is the Caruso family’s habit to sit together for Sunday dinner, catch up with each other’s lives, and discuss family news, and their individual plans and goals.

On this particular Sunday night in September of 2012, Caruso had an announcement to make. For several months, he had been mulling over the prospect of running for Los Angeles mayor and had discussed it with his wife and children. This was the second time Caruso thought about a mayoral run; the first in 2009 against Antonio Villaraigosa.

Caruso seemed primed for a run for the 2013 mayoral election. His company, Caruso Affiliated, and its outdoor shopping center developments, The Grove at Farmers Market in Los Angeles, the Americana at Brand in Glendale, The Commons at Calabasas, The Promenade at Westlake and the Marina Waterside (to name a few), were revitalizing neighborhoods and creating tens of thousands of jobs, while Los Angeles as a whole continued to claw itself out of the pits of recession. Moreover, Caruso was familiar with city politics. At 25, he became the youngest commissioner for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. He was appointed to and then became president of the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners, and was a member of the Los Angeles Coliseum Commission.

With his family’s support, campaign 2013 preparations were made then Caruso assembled his campaign team. Commercials were shot and edited and airtime was bought. A campaign launch date of November 9, 2012, was locked in. Caruso switched parties from Republican to Independent because of his dislike for the political warfare in which the two major parties were entrenched as well as his expectation that an Independent candidate would appeal to a greater number of the city’s Democratic voting bloc.

Now, it was time to reveal his final decision. The dinner table “press conference” commenced. Caruso’s pastor was the first to broach the topic. “Are you going to run?” he asked bluntly.

Caruso said yes and that his mayoral campaign would officially launch in three weeks.

“And one of my kids said, ‘Are you serious? Oh my God, Pop. How’s our life going to change?’ ”

Caruso was hit with a moment of pause.

“It was like, whoa,” Caruso remembers. “They were supportive and said, ‘We’d love you to do it, but we’re so happy as a family, are we going to be the same? Will we still be able to be together as much? Will we have our Sunday night dinners and do all the stuff we love doing as a family?’ ”

Caruso’s moment of pause lasted through the night and stretched into the following week. Was he being selfless or selfish? After more soul searching, he decided against running.

“I could have assuaged their fear, but I thought, ‘Is it fair for me to take away their youth and their moment in time?’ ” says Caruso. “And I said, no, being a dad comes around once. It was a tough decision, but it was the right decision – there’s nothing more important to me than the family unit.”

Family Business

The family unit is a mainstay in Caruso’s life. It not only defines the political decisions he makes but also his business decisions. Caruso Affiliated banks on the family unit when it builds its open-air retail establishments. The Grove, the Americana, The Commons at Calabasas, and his other retail developments are designed to entice families, as opposed to mostly the teen consumer. They afford visitors the luxury of doing more than shopping by welcoming people to watch water fountains dance while dining on a restaurant patio, stroll with the kids, play on the manicured grass, or sit, relax, and daydream.

Fountains and grassy areas are typically considered a drain to a retail operation’s bottom line. “If it grows or flows, it goes” is a common mantra among his competitors, who build typical malls, sans landscaping or fountains, says Caruso. “To them it’s just [added] overhead and expense, but we look at [fountains, grassy space, landscaping] and say it’s an asset. More importantly, it welcomes people to the property and says you’re not just here to shop. Go sit on the grass and have a cup of coffee – let’s use it to watch a movie at night.”

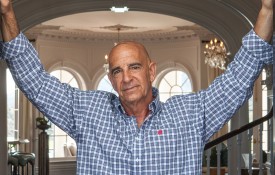

Standing on the outdoor balcony patio of his office, “The Grove” lettering backdrop is illuminated behind Caruso. “It’s cool to envision something, build something, and then see people enjoy your work,” says Caruso.

Over the past year he’s been somewhat of a sage for the open-air retail establishment, extolling its virtues at development conferences such as the National Retail Federation’s 2014 “Big Show,” where he was the keynote speaker. His message: “The Traditional Mall is Dead; Retail is Timeless.” Open-air retail is the future because it creates an experience that connects people to their surroundings, other people, and in effect it becomes a community center, he reasons.

“They’re married to the natural rhythm of how humans function: You’re outdoors, you see things, you hear people. People want to feel a sense of community,” says Caruso. “As much as we talk about market share, we [just as much] talk about how much heart share we control: What’s the emotional connection of our guests to our properties?”

His affinity for trolleys falls in line with that mission. The Grove features a tracked trolley that creates a sense of nostalgic whimsy as passengers ride from one end of the outdoor expanse to the other. Caruso envisions a trolley system that will carry people outside The Grove, up Fairfax Avenue, down Third Street, west to the Beverly Center, and to stops in between. He insists the trolley run on a track rather than rubber wheels, which is much more expensive and cause for a great deal of street construction. And he’s willing to back his belief with his wallet.

“It would be the best investment I can make in the future of this area,” he reportedly said in June. To which Los Angeles Councilman Tom LaBonge said, “I’d like to get it done right now. If Rick is hot on it, I’m going to go.”

It is easy to fall lock-step behind Caruso because of his stellar record as a developer. Caruso Affiliated has never failed to get a project approved on which it has embarked, except for one project in Arcadia that fell through due to the landowner filing for bankruptcy, explains Caruso. This event posed as just a speck in what has grown into today an unblemished development history of the company.

Caruso Affiliated’s foray into the luxury apartment space at 8500 Burton Way – an eight-story glass tower that boasts 5-star concierge amenities – is an architectural gem that glistens on the corner of La Cienega and Burton Way. Completed in 2013, the property is full and has a sizable waiting list of prospective residents.

It Can Be Done

Caruso thinks analytically and is solution driven – a trait he reinforces at every rung of the company hierarchy.

“I have a couple rules around here and one is, there’s a solution to every problem,” Caruso says. “So whenever we face an entitlement issue, a zoning issue, a business issue, I always say to the team, ‘Why are we having that problem? From where does that problem originate?’ You’re always going to find a solution to the problem once you find out the background behind the problem.”

The 54-year-old developer regularly faces problems because his business model is to succeed where others have failed. For instance, a mall had been planned in The Grove area for years, but developers never broke ground. The entitlement process was snarled, and the community and city officials were fighting each other.

“For us it was about figuring out what everyone was against; solving those problems. And the minute we solved those problems we figured out what we could build,” says Caruso. “We’ve taken that approach on everything.”

Focusing on the shopper’s experience beyond the purchase point makes Caruso Affiliated’s developments attractive to both shoppers and high-end national and boutique retailers. That Caruso Affiliated is involved with the day-to-day management of its properties is part of its allure, says Caruso.

“We’re one of the few, if not the only developer that will double down on their property,” he says, emphasizing that retailers can trust that a Caruso Affiliated property will be maintained to the highest standards and as a result attract a high number of shoppers because his company is as invested in the property’s success.

The Grove’s anchor store is Nordstrom, which spent between $30–$40 million on its building, Caruso estimates. “They’re not going to do that in an old, tired mall because it [an old, tired mall] is an inconsistent statement you’re making to your customer,” Caruso says.

The firm is making a push into San Diego and Northern California. The day before his interview with CSQ, Caruso returned from San Francisco where he and his executive team walked Fillmore Street, looking at architecture and retail establishments. In total, Caruso Affiliated has “a couple billion dollars’ worth of projects in our pipeline today — all of which are in California . . . And we’ve never overleveraged, so our debt-to-asset ratio is under 40 percent.”

One of those projects is in Pacific Palisades and has been in the planning stages for 10 years. Caruso sees the final development transforming the area’s main street. But before he can start, he has to earn the trust of the area’s stakeholders. The challenge is to engage with the local residents, business owners, and city officials to create a street that feels organic to the area. Caruso plans to redevelop from the street up – the sidewalks, the street lights, the trees, everything. “People have to walk out of their homes in the Palisades, walk that street and say, ‘This is my town.’ ”

To ensure the organic feel fits the Pacific Palisades community’s desires, Caruso planned community meetings to ask residents to voice their desires. His first scheduled community meeting was February 26. “It’s like an artist painting,” explains Caruso, waxing a little poetic. “You go layer by layer and by the time you’re done with the layers you have depth. It has to weave into the fabric of the community so that it feels organic.”

Caruso enjoys the community created when building a project nearly as much as he enjoys the end result. But when he can combine his passion for creating community with his passions for building and boating, he is near his zenith.

The result of that perfect combination was Caruso’s 216-foot-mega-yacht, Invictus, built in the Delta Marine shipyard in Seattle. Built in the midst of the recession, Caruso specifically chose Delta Marine because it is an American shipyard and wanted to create jobs for American workers.

“It bothered me that the yachting business had left the U.S. I wanted to bring jobs into the U.S., and we employed thousands of people for a couple years — mill workers, painters, pipefitters, electricians, and on and on,” Caruso says.

The day they rolled Invictus out of its shed, Caruso threw a barbecue to thank the employees of Delta Marine and their families and handed out T-shirts with the words “Invictus: Made in America” printed on the front.

“The collective pride was palpable,” Caruso says.

“A big pipe worker, a guy who looked like he could rip your head off, was [in tears] … there was such a sense of pride in building [Invictus],” Caruso remembers. “It showed we can accomplish great things if we determine to accomplish our goals.”

Invictus’ success motivated others to build their yacht in the United States. Following its completion, a Middle-Eastern group went to Delta Marine to build their yacht, Caruso says.

A Rick Caruso mantra

A Developer’s Roots

Caruso’s interest in building and owning dates back to his childhood. His parents’ home overlooked Los Angeles, and a young Rick Caruso would look at the city and point to the buildings he wanted to buy. His father, a World War II veteran, “worked hard, some would say too hard,” to build a car sales business, eventually founding, then selling, Dollar Rent A Car. His grandfather worked as a coal miner setting dynamite in coal mines; Caruso remembers him as a gardener. Witnessing their hard work and the familial atmosphere his father created at the workplace, he says, served as the blueprint for his leadership style with Caruso Affiliated.

But first he would lose his job. A few years out of law school and working as a real estate lawyer, Caruso was blindsided when the firm shut down. Searching for solutions, he found himself asking his wife, Tina, what he should do next.

“We were living in Westwood and we went to the McDonald’s on Santa Monica Boulevard west of Beverly Glen and sat there,” Caruso remembers. He was only a couple years from earning his law degree. “I said, ‘I don’t know what I’m going to do.’ And it was Tina who said, ‘You love real estate, do it. We’ll figure it out.’ ”

His first real estate purchase was a small, “run down,” duplex in Westwood on the corner of Midvale and Massachusetts Avenues. Caruso was the gardener, maintenance man, painter, and leasing agent. He learned the value of his property increased when he maintained its infrastructure and beauty, enabling him to justify rent that was higher than nearby, comparable properties. Caruso held on to that property until 2012 and reluctantly sold after executives at Caruso Affiliated detailed the time being spent maintaining it.

“That was the only [property] I ever sold,” Caruso says.

Being born and raised in Los Angeles, Caruso involves himself with all parts of the city, including its less-fortunate areas. His inspiration for philanthropy comes from his Catholic faith and respect for Pope Francis.

“My favorite saying from Pope Francis is, ‘A shepherd should smell like the sheep,’ ” Caruso says. “That’s what I’ve always taught my kids. Go to Watts and to Skid Row and work with the children, because you can’t understand the problems unless you’re down there with them. Real charity comes from being amongst the people.”

Caruso’s children volunteer at St. Lawrence School in South Los Angeles and on Skid Row and the family contributes to and financially supports Para Los Niños, a nonprofit organization that provides educational opportunities and social well-being for children in LA’s most impoverished areas.

“The children at St. Lawrence have taught our kids to have a sense of humility,” Caruso says. “Most of those kids are surrounded by drugs, poverty, and violence and yet they come to school and they have a smile on their face. So it doesn’t matter the car you drive, the house in which you live, or the money you have, you can be a happy person because you’re positive about life.”

He sees opportunity for growth throughout Los Angeles but advises city leaders to focus on individual neighborhoods, celebrating and understanding what makes them and their issues unique.

“The biggest problem . . . is that the whole city is viewed as one and the city is not one,” Caruso explains. “What’s right for West LA is not right for South LA, or East LA, or the Valley. [City officials] should break down each area’s needs and when you start doing that, the development and redevelopment make more sense – transit issues make more sense.”

Always looking for areas where his birth town can be better, Caruso says to bring business and redevelopment to South Los Angeles, he would engage the Department of Water and Power and its “enormous cash flow.”

“Have DWP invest in South LA with infrastructure, then go to manufacturers and say we’ll eliminate the use tax, and we won’t charge a utility tax, and we’ll give you free utilities for the first five years,” he proposes. “Now that we’ve put in the roads, the power, and the fiber optics, you put your manufacturing plant here. And the DWP is going to get paid back, because after five years they’re still going to be there.”

Such an audacious plan would require city leadership that is “risking their jobs every day,” Caruso says. “Elected officials have a disease,” he adds. “They don’t risk their jobs every day; they work to protect their jobs every day. Don’t worry about reelection,” he challenges. “Start celebrating neighborhoods and solving problems.”

Caruso, as an Angeleno native with more than $1 billion in assets invested in the city, has both personal and professional reasons to challenge Los Angeles’ leaders to be better and to solve the problems he sees.

“I don’t have the luxury of leaving California – I can’t pick up my asset base and move,” Caruso says with a chuckle. “I have to be committed to it, and I believe and I am proud of Los Angeles.”

Caruso is involved with Operation Progress, St. Lawrence of Brindisi School – part of his commitment to providing education and mentorship opportunities to the kids in the Watts community

Leaving His Legacy

Being handpicked to sculpt a billionaire’s children is far from the norm, but for French sculptor Delesprie, that’s what happened. Delesprie was commissioned to sculpt Rick Caruso’s children, who can be found in bronze form frolicking on the grounds of Caruso Affiliated’s many properties.

What started as a brother and sister selling lemonade under a shade tree on a grassy knoll by a lazy pond has blossomed into a tremendous working relationship. Caruso and Delesprie, both masters of their crafts, have recognized the unique and unquestioned talent in one another and have opted to stay together, for the kids. As a result, the Caruso children, bronzed exquisitely, will live on across the region as timeless reminders of the importance of family.

Some of her most famous works are seen by millions of people year after year. Whether visiting the Gene Autry Museum, catching a game at Angel Stadium, or visiting any of Rick Caruso’s properties, you’re bound to walk past a Delesprie work. The meticulous details she captures in a 30-inch tall piece can take up to 1,200 hours to create – the truest testament to Delesprie’s painstaking dedication to her craft.

Her most famous piece is the 35-foot tall sculpture of two angels, placed above a marble column at the heart of The Grove in Los Angeles. The piece, given that her name translates to “from the spirit” is appropriately titled, “Spirit of Los Angeles.”