Lucas Keller isn’t afraid to change direction. He’s currently celebrating 11 years of heading his global talent management firm, Milk and Honey, whose songwriter and producer clients have had some of the biggest hits of the decade very recently Dua Lipa “Levitating” to Post Malone and Morgan Wallen “I Had Some Help” to Kendrick Lamar and SZA “30 for 30” to Charli XCX’s viral Brat album and a #1 last week month with Alex Warren’s Ordinary, just to name recent hits. All of this not including chart toppers from recent years like “Despacito” from Justin Bieber, Daddy Yankee and Luis Fonsi and “Sorry Not Sorry” from Demi Lovato, or Christina Perri’s “A Thousand Years” and James Arthur’s “Say You Won’t Let Go.” On the football side, clients like Travis Kelce, and Courtland Sutton. Still, there are more interesting things to say about Keller’s story than a few name drops.

Milk and Honey also represents clients who earn a combined 12 Grammy nominations on average each year. The firm has now branched out into sports, representing more than 80 athletes, including many in the NFL.

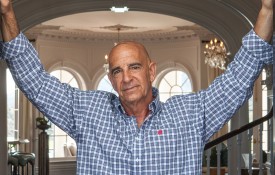

Photo Credit: David Fouts

HOMETOWN BEGINNINGS

With the entertainment industry centered in L.A., Keller didn’t exactly have geography on his side. He was born 2,000 miles away, in Wisconsin.

But even Wisconsin has music, and Keller started playing the guitar at age 6. He was part of various punk and heavy metal bands growing up, and dreamed of making it as a musician. By the time he reached college, he thought it probably wasn’t going to happen.

Fortunately, he found that he did have a skill set that could launch his career in the music industry, and started working for a band.

“I didn’t even know the difference between a manager and an agent,” he says. “I was just the guy that gets things done, that helps out. I would carry amps; I’d book their tours; I put their records out.”

What Keller didn’t have in experience he made up for with hard work, cold emailing promoters and record labels to build his network from scratch. He had to be doing something right, because those bands went on to secure record deals—some selling 1,500+ tickets across the Midwest. He even cold reached out to Steve Jobs which turned into a global itunes campaign for a non-profit project he was working on.

“When you’re young, you don’t see limitations the same way as when you’re older.”

After building a book of artists under his management, he received two job offers: to work for My Chemical Romance’s manager in New York, or for Kid Rock’s previous manager in Chicago. He chose Chicago, where he stayed for four years while managing various rock bands.

In 2009, a friend who was managing the All-American Rejects convinced him to move to L.A. to join a company called The Collective and his career took off in a new direction.

L to R Courtland Sutton WR Denver Broncos, Lucas Keller Milk & Honey CEO / Founder, Dave Frank Milk & Honey Sports partner

VENTURING INTO TALENT MANAGEMENT

The Collective was a fast-growing music, TV, and film company with various actors, artists, comedians, and digital talent under its wing. It had a team of 30 when Keller first joined, but had ballooned to 250 by the time he left. It was a huge step up from his team of four back in Chicago, and was a different experience being inside a large media management company. The company’s music department represented Linkin Park, Kanye West, Slash from Guns n Roses, and Enrique Iglesias to name a few. It was at this company that Keller would learn a lot of what became the building blocks of Milk & Honey.

He also started managing songwriters and producers, which turned out to be a career-defining shift. Although much of Keller’s time at The Collective (and his first years of Milk and Honey) was artist-focused, his success went up a notch once he switched to representing writers and producers.

“Sometimes life does it to you,” he says. “You say, I really want to do this thing, but there’s this thing over here that should be chasing because I’m better at it, but you’re pushing to do this other thing because that’s what you’d thought you would become” And so one day I said, ‘Let’s not manage artists anymore.’”

He had just finished a long run with Scott Weiland (Stone Temple Pilots), recently won a Grammy with Jimmy Cliff, and had burnt out on artist management.

Milk and Honey now represents about 75 writers and producers, across practically every possible genre and around the world. The first office was in Los Angeles, followed by Brooklyn, then onward to Nashville, and London—and, later, Dallas when the sports agency was launched.

Keller with business partner Nic Warner

REFLECTIONS ON THE INDUSTRY

During his time in the industry, Keller has been involved in some seismic shifts. One was the move toward streaming, and another was the increased profitability of selling music catalogs during the COVID pandemic. Milk and Honey sold some meaningful catalogs that today total over $300 million in aggregate sales.

Keller admits that it wasn’t something he anticipated beforehand. “I think when we started the company, we were naive enough to just want to get songs on the radio and have big songs with artists,” he says. “We didn’t think that we would sell those rights later.”

The realization of the true arbitrage of music rights with streaming, and Goldman Sach’s Music Is In The Air Report which landed right at the beginning of the pandemic changed the game. Folks realized that these rights were more valuable than they thought, and the ability for a songwriter, producer or artist to sell their catalog and get a capital gains tax advantage plus the low cost of capital – well “it was just a perfect storm that will never happen quite the same way again.”

Back in 2002, getting eight times a music catalog’s value to sell the music rights was deemed as highway robbery. Yet during the pandemic, many catalogs reached multiples of 20 and more, with 30X on blue chip legacy catalogs. While Keller says he would advise any musician to resist selling their catalog too early, it was a huge moment for his business.

“We accumulated this really amazing list of buyers, which I don’t think most people have,” he says. “I think we’re around 170 buyers globally now, I haven’t met anyone with that quantity of relationships.”

This led to the company specializing in selling catalogs, particularly becoming experts not just in selling older vintages, but driving value for newer songs too which many sellers will not touch.

Although he’s pushed boundaries throughout his career, where does Keller stand on some of the more contemporary issues facing the music world? When it comes to blockchain, he remains cynical.

“Anytime someone says tokenize, coin, crypto, blockchain, NFT, my eyes roll back into my head,” he says. “For a while I was probably getting a deck a week from a company about how we’re going to put music rights on the blockchain.” He says he’d be happy to move into that space once the technology is ready, but he’s not interested in building the system.

He also predicts that federal laws will change when it comes to consent decrees, and that various changes will open up music collection to the free market.

“It can only get better, so long as the people that control these systems pay out a fair rate to creators, which has been an issue with the streaming services,” he says. “I’ve been really vocal about my dissatisfaction with how Spotify treats songwriters and publishers. And so there are still some issues to work out there.”

When it comes to the prickly issue of AI. Copyright in the music industry has become increasingly contentious over the last few years, and AI could muddy the waters further.

“Companies like Suno and Udio that really taken copyrights from the major label catalogs and trained on those catalogs—my argument is that’s like a billion micro infringements,” Keller says.

With artists facing so many potential challenges, Milk and Honey is doing what it can to guide musicians through this landscape.

But there’s certainly plenty to be optimistic about. Keller is keen to point out that a large percentage of the world still doesn’t have high-speed internet or streaming music, and as they go online over the next few decades, the music business could double.

Photo Credit: Blake Young

SWITCHING INTO SPORT

As if it wasn’t enough to manage dozens of artists and genres in multiple different countries, Keller is now juggling sports representation too.

It might seem like a bold move, but Keller admits it wasn’t exactly something he masterminded. Rather, he was talking to an old colleague with a lot of sports agent friends who suggested the idea. If the future of the music industry looks bright, Keller believes things for the sports sector will be blazing.

“I will say that there’s no question that athletes are going to get paid a lot more money in the next couple decades,” he says. ”Look at the changes in the network deals, and at the name/image/likeness space—it’s going to be really exciting.”

Keller’s firm is currently focused on football, with about 40 NFL athletes currently on his books.

The natural follow-up question for many might be which industry he plans to enter next. Formula 1? Chefs? However, rather than branching out, Keller hopes to go deeper.

Some of his biggest goals going forward include helping athletes to create ventures, diving more into the asset ownership space, and possibly raising a fund on the music side.