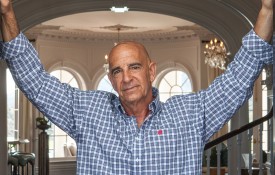

After decades spent running tech companies, Spencer Rascoff is returning to his early roots in journalism and finance to launch a site dedicated to covering the Los Angeles tech scene. It’s the latest endeavor for someone who’s used to taking big leaps. CSQ talked to Rascoff about his formative experiences, the ups and downs of running startups, and what comes next.

You’ve founded several dot–coms, but your background is in finance. How did those two worlds come together for you?

Actually, I wanted to be a journalist. I grew up in Los Angeles and went to Harvard-Westlake, where I was the editor in chief of the school paper, The Chronicle. I went on to Harvard University and did summer internships at Bloomberg and NBC News. Based on that, I realized I was more interested in business than journalism, but journalism always stuck with me. I ended up on Wall Street after college, in 1997 working in M&A at Goldman Sachs. I loved the fast-paced, high-stakes environment, but I decided I didn’t want the life of a banker. I was always looking at the people who were 10 years my senior, and when I looked at the lives of those bankers, I knew it wasn’t for me.

I left New York and moved to San Francisco, where I got a job at Texas Pacific Group [TPG]. I had a similar experience, where I realized I didn’t want to be in private equity, mostly because I wasn’t interested in the complex financial structuring of private equity returns. I was more interested in company and team building.

Fortunately, while I was there, we were incubating an idea for a discount travel company. This was in 1999 around the first internet boom. Priceline was huge at the time, and to get started, they had given around 25 percent of the company to Delta Airlines in order to get inventory. Once Priceline went public, other airlines were interested in getting into the space.

TPG had bought Continental and America West airlines and owned part of Northwest too. We worked to build partnerships with six airlines—all of the big ones but Delta—so that we’d have their preferential inventory of tickets. That’s how we started Hotwire. I left TPG to launch it, along with one of my colleagues, who became the CEO. My job was everything else. I think my official title was co-founder and VP of corporate development, which sounded vague enough to allow me to do anything, which is what’s required at a startup.

We launched in 1999, and things were pretty good until 2001, when the bubble burst, and there was a lot of second–guessing around working at a startup. Things got worse for the travel industry around 9/11 too.

Spencer Rascoff co-founded Hotwire, Zillow, and now dot.LA.

Also, this isn’t something that I talked about until a few years ago, but 9/11 was a dark time for Hotwire. The hijackers had used the site to purchase their tickets. Only our senior leadership knew this because the FBI had come to us about it. I had an awful sense of guilt over it, which was exacerbated by the fact that I had given a speech at the Hilton that was crushed by the Twin Towers and flew home on 9/10 on the same flight that was hijacked the next day.

From a business standpoint, things were hard too. In 2001, we laid off a significant portion of the company. We did a down-round with TPG, which wiped out a lot of employee ownership and was an important lesson for me. Hotwire rebounded by 2003 thanks to a lot of hard work and employee grit. We retained Goldman Sachs to go public, but during the IPO process, Expedia, which was being run by Barry Diller and IAC, came to us and wanted to buy it for $685M, which was the largest all-cash purchase of an internet company at the time.

About two years before that, my girlfriend, who is now my wife, Nanci, moved from San Francisco to Seattle for medical school, so it worked out well that a Seattle-based company like Expedia had acquired us. I moved there to work at Hotwire’s new parent company, but after a couple of years, I wanted to do something more entrepreneurial.

It’s a big jump to go from a travel-booking site to a real estate–listing site, with the launch of Zillow. How did that idea come to you?

It’s actually not so different. I left Expedia in 2006 with a few other executives, and we spent a couple of months in a conference room thinking about ideas. We had two, both of which were born from personal frustrations and experience. We were buying homes at the time and were frustrated that basic info like what the seller paid for a home was inaccessible. It was public but locked up. We wanted to put a light bulb over real estate, which is similar to what we had done with the prices of airline tickets at Hotwire. Previously, only travel agents had had access to special fares, and we democratized those.

Our other idea was essentially a file–saving cloud—basically Dropbox. We were all moving hard drives of family photos and were in need of file transfer and storage. “Cloud” wasn’t an idea yet, but we decided against it because we thought that the big tech companies like Yahoo, eBay, and AOL would offer it at a low price we couldn’t compete with. We never thought it would actually be Amazon, Google, and Microsoft to lead the way with cloud, but we knew it would be too hard for a startup to compete with giants. Amazon has essentially won in the cloud space because of their huge scale. Dropbox and Box are successful but can’t compare.

We chose real estate because we thought the industry lacked transparency. Before Zillow, only real estate agents had access to sales prices and listings data. We thought we’d put everything on the web and people would use it—but we had no real business model. We knew though that real estate was 20 percent of the GDP, and the business model would emerge.

What were the early days of Zillow like?

When we launched in 2006, we had 1 million users in the first day, now they have about 200.7 million average monthly unique users who visit Zillow Group’s websites and mobile apps. Even by today’s standards, that’s big. Zillow came out with such a bang because it’s voyeuristic. You can Zillow your girlfriend’s house, your boss’s house… people wanted to look up the houses of everyone they knew. The first two years were great. By 2008, we had 200 employees, but then the financial crisis hit. Right in our industry. It was almost like Hotwire all over again, and we had to lay off about 25 percent of the staff. However, we avoided a down round this time. Our employees locked arms and stuck with it. Their grit served us well, and by 2011, we went public.

Rascoff’s latest endeavor is Los Angeles tech news site dot.LA.

How did Zillow evolve?

In 2006, I started as the CMO at Zillow and was CEO by 2008, and our entire team was extraordinary. To build Zillow, we tapped into thousands of different records, MLS feeds, census data, and various industry databases. We bought a lot of transaction data and put it online. No one had ever done that. That innovation was eye–opening to early users.

The big accelerator though was mobile. In 2006, there were no smartphones, but in 2007, Apple launched the iPhone’s app store. I remember I was at my desk and saw Steve Jobs talking online about the app store and explaining how companies would be able to offer their own apps for iPhones. As soon as I saw that, I ran over to my co-founder, and we quickly pivoted to mobile. We switched the whole model and dropped “.com” from the name. We were the first major real estate app on iPhone. Everything took off more from there. During my time there, we acquired 16 different companies, including Trulia, for $2.5B, grew the team to 4,500 people, and expanded the value of the company to over $10B.

When did you feel successful?

Only very recently. Two years ago, maybe, the tide started to turn for the word “Zillow.” In the early days, I used to have to explain what it was. Then, maybe five years ago, people would recognize it. But only about two years ago did it enter the mainstream lexicon, and it tipped as a brand. When you start to see unpaid product placements for it on TV and film, it means some writer and director chose to keep it in, and that means it’s a product that people know and love.

At the dot.LA launch event with Mayor Garcetti in January, hosted at the offices of FabFitFun.

You recently retired from Zillow, and you’re only 44. What do you do next?

In February 2019 I finally retired because my family had moved back to Los Angeles in 2016, and I was tired of commuting back and forth from Seattle. I stayed “retired” for about five minutes though. I immediately started investing in early stage tech companies, and I taught a course at Harvard Business School about how to run a tech company.

Earlier this year, I launched dot.LA, which is a news site about the tech industry in Los Angeles. The more I got familiar with the L.A. tech scene, the more impressed I was. There’s a huge number of unicorns, incubators, and a lot of VC capital, yet very little journalism about it. There’s almost nowhere to read about it. Our goal is to be the town crier for L.A. tech. There’s a huge period of growth in L.A. tech, and we’re covering everything from fundings, new feature releases, M&A, trends, events, webinars. Right now, dot.LA is the most widely read tech publication for Los Angeles. It’s a low bar, but we got it.

Separately, I’ve started another company, which is still in stealth mode. My goal is to start more companies, maybe three to five per year, and act as a one-person venture studio in an active co-founder role, and get a broad purview across multiple companies.

You have tremendous drive. Where does that come from?

I was a straight-A student in school. Total nerd. I had great relationships with teachers, and several of them are still my friends. My high school journalism teacher, Kathy Neumeyer, put me in touch with another Harvard-Westlake graduate, Sam Adams, who was also the editor of The Chronicle, who is now my co-founder and CEO at dot.LA.

A big thing I got from school was teambuilding and work ethic. Hitting deadlines and working hard under pressure. Some people get that in sports, but I got that in the newspaper. (Although I did play sports too – tennis, cross-country and track. So not a total nerd, I guess.)

Being editor was about a five-hour-a-day job. This was pre-technology too, where we were cutting columns with X-Acto knives and sticking them to boards using hot wax. We had a staff of about 40, which were also my peers. That was an important skill I took with me to Hotwire, which I started when I was 23. (I was 30 when I started Zillow.) At Hotwire, I was managing people decades my senior. What I learned from the paper is that you earn respect by working hard.

Another big drive for me was losing my brother when I was 15. He passed away the day before graduating Harvard School [before it merged to become Harvard-Westlake]. He was also the editor of the Harvard News and had pulled an all-nighter to wrap up the last issue. He got into a car accident on the way to the printer.

I really kicked things into high gear after his passing. I became even more performance driven following his death.

What lessons learned from your previous companies are you taking with you to dot.LA?

Any wrong decisions I’ve made in the past have been generally caused by overreacting to near–term information. Jeff Bezos talks a lot about two–way–door decisions and one–way-door decisions. You can either go through and come back, making a decision that can be undone, or make a decision that there’s no going back from.

It’s important to know which kind you’re making. With dot.LA, we were planning on building an events business for revenue, but Covid upended that. So we shifted to free webinars that will eventually be supported by sponsors. If it’s not working, we can revisit. It’s a two-way decision. We’ve raised enough money for about two years of runway, so we’ll see how a business model emerges from that.