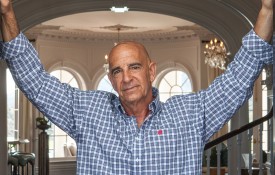

Plenty of stand-up comedians have gone on to carve out lucrative, multifaceted careers in Hollywood. Then there’s Byron Allen.

The 58-year-old owner and CEO of Entertainment Studios recently agreed to acquire 15 broadcast television stations for approximately $455M, part of a multiyear buying spree that includes investing, in partnership with Sinclair, $10.6B in Fox’s former regional sports networks, and spending more than $300M on The Weather Channel.

Now, as he prepares to go in front of the U.S. Supreme Court on November 13 as part of a $20B discrimination lawsuit against cable giant Comcast Corporation, Allen has firmly established himself as one of the most powerful—and consequential—media owners in Hollywood.

Television has reinvented itself numerous times since Allen made his national TV debut before he even graduated from high school. The rise of cable and then streaming video reshaped the television landscape, launching new visionaries to prominence and humbling some who had been riding high for years. Even as the future of TV remains to be determined, Allen’s rise has been constant.

The man we’ve seen interviewing celebrities for decades is now more powerful than most of the marquee names he’s interviewed.

On The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson in May 1979, when Allen was 18.

Allen seems to have an innate ability to know which way the winds are blowing and position himself accordingly. That vision and confidence has sustained him, from the early days when investors and bankers wanted no part of his fledgling company, and he had to sometimes skip meals, to now, when everyone who matters is banging on his office door looking for a meeting. But he wouldn’t trade those tough times for anything.

“It’s like going to the gym,” he says. “A guy who only has to bench press 50 pounds is not going to be as strong as a guy who’s forced to bench press 500 pounds. That resistance is what made me unstoppable.”

Allen the Family

Byron Allen Folks was born in Detroit, Michigan, in 1961 and moved to Los Angeles at age 7 with his mother, staying put after what was originally supposed to be a two-week vacation. They slept on friends’ and relatives’ floors.

Not long after, his mother began pursuing master’s degree in cinema and television production from UCLA. While a student there, she convinced NBC to start an internship program, with her as the network’s first-ever intern.

That led to a position as a tour guide at NBC’s Burbank studios, where an elementary school-aged Allen started hanging out and falling in love with the business, watching legendary comics like Redd Foxx and Bob Hope film their sitcoms and specials, and Johnny Carson host The Tonight Show.

“I fell in love with television,” Allen says. “The art of making television, and the business of making television and being a comedian.”

While still a preteen, Allen started doing warm-ups and wrote a spec script for Sanford and Son. The sitcom didn’t pick up that script, but Allen was able to pull the jokes from it to create his first comedy monologue.

David Letterman, Jimmie Walker, and Byron Allen, age 15 at a writing session for Walker’s standup.

In the summer of 1976, Allen was on set watching Gladys Knight & the Pips perform, and she had a young comedian on the show who brought the house down. Allen knocked on the comedian’s door to ask how to break into comedy and was told to go to the Comedy Store on the Sunset Strip and to watch his new sitcom. The young comedian advising Allen was Gabe Kaplan, and his new sitcom was Welcome Back, Kotter.

Allen started performing at the Comedy Store, “to a room with four people and 100 chairs,” but since he was underage, he had to stand outside or in the back so the club’s liquor license wouldn’t be jeopardized. He also had to use the currency stand-up comedians were paid with at the time, two drink tickets, to buy water or soda. But that’s where he got his big break.

A comedy writer named Wayne Klein saw Allen perform one day and asked him who wrote his jokes. When Allen said they were his own, Klein asked for his phone number.

Allen got a call a week or so later from Jimmie “J. J.” Walker, then-starring on the hit show Good Times, inviting him to join the writing team. Allen was 14 years old.

“I walked into Jimmie’s apartment, and sitting there was David Letterman, who had just driven out from Indianapolis in a red pickup truck; Jay Leno, who was sleeping in his car; and Marty Nadler, who went on to produce Laverne and Shirley and Happy Days.” Allen says. “A lot of phenomenal folks.”

Soon after, Allen sold his first joke to Walker for $25. He still has that check framed in his office. More importantly, being around that level of talent forced him to up his game.

“In that room, it was like Comedy University,” Allen says. “The art of creating a thought, a picture that everyone gets at the same time that creates laughter. You’re learning ways to extract funny out of any and everything.”

That training got Allen to the big stage. At 17, a talent scout for The Tonight Show offered him the chance to appear on the late-night staple. Allen turned him down, because he was still a high school student.

“I wasn’t training for an appearance, I was training for a lifetime,” he says.

The second time he got the offer, Allen was ready. When he appeared on Carson’s The Tonight Show in May 1979, one week before graduating from high school, he became the youngest-ever stand-up comedian to perform on the show.

A Star Is Born

Allen seized the moment and crushed it. While his classmates were figuring out college majors, he found himself deciding between lucrative TV offers. Joan Rivers was one of those who came calling, looking to do a sitcom with Allen.

But he was more interested in a show called Real People, a proto-reality program that focused on everyday Americans, not celebrities.

“I’m very numerical and mathematical,” Allen says. “There were only three networks at the time, ABC, NBC, and CBS. There’s 66 hours of prime-time television between them. Out of the 66 hours, this is the only hour that’s different from the other 65 hours of prime-time television. And I believe this show will work because it’s different than the other 65 hours.”

At an event with Warren Buffett in 2018.

He was right. Allen appeared on Real People from 1979 to 1984, traveling the country and interviewing everyday folks. He also attended film school at the University of Southern California but didn’t finish. There’s only so many hours in a day, even for Byron Allen.

During that time and after, Allen toured widely as an opening act for everyone from Lionel Richie to Dolly Parton and Sammy Davis Jr. He had made it to the biggest stages. Now, it was time to take on the corner office.

Building a Business

Even as a youngster workshopping jokes, Allen always wanted to be more than a performer.

“I always figured it wasn’t show business, it was business show,” Allen says. “I always focused on the business side.”

So while he was touring the country making crowds laugh, he was already thinking about how to monetize that gift.

In January 1981, while still a teenager, Allen attended his first National Association of Television Program Executives (NATPE) convention in New York, where TV and ad executives meet up to talk shop. There, a chance meeting with an executive gave the young comedian a front-row seat to the launch of another soon-to-be hit, Entertainment Tonight.

“I learned how to sell television shows directly to TV stations,” Allen says. “I made a lot of friends with a lot of people who owned and operated TV stations.”

After over a decade of hosting TV shows and entertaining crowds across the country, Allen decided it was time to strike out on his own. He started what would become Entertainment Studios from his dining table in 1993.

On the way to NATPE with Norman Lear in 2018.

“I started by calling all 1,300 television stations in the country,” he says. “I asked them to carry this once-a-week, one-hour show where I’m interviewing seven movie stars talking about their latest projects.”

Allen sat at his table for about a year, sunup to sundown, asking these stations to take the show, Entertainers with Byron Allen. He offered the programming for free, and a 50/50 split of the 14 minutes of built-in commercial time.

“On average, they said no about 40 to 50 times each,” he says.

Allen persisted, and after tens of thousands of rejections, he got about 150 stations to say yes, covering every major market.

Allen says he was told by Tribune Media that if he got to about 75 percent of the country, they would sell his ads and give him a $400,000 advance. Allen got 90 percent of the country, but Tribune backed out of the deal. Allen wasn’t going to pull out now, so he put on the show himself.

That wasn’t the only hurdle: A TV station called Allen and said salespeople from a major studio had told the station Allen was calling from his dining table in his underwear, and his fledgling show wasn’t going to last long.

Allen called him back and confessed to being at his dining table in his underwear. But he was more resolute than ever that he would succeed. It was personal now.

“Tell the boys I’m never going to cancel the show,” he says. “I’m never going to cancel it because I’m never going to allow them to walk into another TV station in the United States of America and convince the general manager to have doubt in me. One day you’ll have more faith in me than in all the studios combined.”

Entertainers with Byron Allen recently celebrated its 26th year on the air.

A Media Empire

Allen may be flying high today, but it was touch and go for a long time during the early days of Entertainment Studios.

“When Tribune reneged on me and they did not give me the money, I decided to go forward, and it was really tough,” he says. “There were days I didn’t eat. There were days they turned off my phone. My home went in and out of foreclosure 14 times.”

One thing they couldn’t take away from Allen: his relationships with the stars he was interviewing. That’s what saved him.

“I sat with all the heads of the movie studios and I said, ‘You know, I’m interviewing all your movie stars and I’m talking about your movies and I’m showing your movie clips. I really want you to support me because you guys are each spending $200M to $600M a year buying advertising time, and I’m a one-hour commercial promoting your movies. So please support me so I can be there to support you,’” he says.

Then he went out and started signing up other industries. Cars. Soft drinks. Packaged goods. He was off and running, with plenty of food in the fridge and a mortgage payment that cleared every month.

“I went to the ad agencies and I went to the boards of directors and I went to the chairmen and I went to the CEOs and I went to the chief marketing officers,” Allen says. “I just became pretty much a Category 5 stalker. Finally, I just broke in and kept going.”

Pretty soon, Allen had compiled an extensive library of interviews. That gave him another idea.

He put together a one-hour special of interviews with athletes, including Michael Jordan, Steve Young, Oscar De La Hoya, and Grant Hill. He called the major networks, which said he could buy the time for $250,000, but was only guaranteed 75% of the country, due to a significant amount of preemption from affiliate networks.

That wasn’t good enough for Allen. He called the affiliates directly and ended up with carriage in every market. Then, he took advantage of the commercial relationships these athletes had and started offering advertising time to blue-chip companies, who were more than eager to snap it up. This was different.

“My advertising at that time was 1-800-Spray-on-Hair,” he jokes.

Allen produced and edited the show for less than $20,000. The special brought in over $1M in ad revenue.

The Next Level

Allen kept growing, “smiling and dialing for dollars,” as he says. Today, Entertainment Studios has 65 shows on the air, including Comics Unleashed with Byron Allen, The American Athlete, and Funny You Should Ask.

But he had higher ambitions. high-definition, in fact.

In the late 2000s, Allen came across a New York Times article saying that Verizon was going to invest $20B to launch 150 high-definition channels. He wanted in.

Allen got a meeting with Verizon executives and said he wanted to launch 10 channels. He did it with a sales pitch that took on Hollywood’s wasteful spending and provided an alternative.

“When I send camera crews to Pebble Beach to shoot the car show, Concours d’Elegance, I don’t want to just have them shoot the car show for our car network, Cars.TV,” Allen says. “I want them to also shoot the resorts up there for our travel network, MyDestination.TV, and shoot the chefs up there for our cooking channel, Recipe.TV, and shoot all the movie stars and celebrities who come up there for the car show for our entertainment channel, ES.TV.”

Allen didn’t get his 10 networks, but was given six, making history by launching them all simultaneously in 2009.

As his business has grown, Allen has made a string of acquisitions as he works to build Entertainment Studios into a comprehensive media company. This year, he has agreed to buy a total of 15 network TV affiliate broadcast stations in two separate deals. And in 2015, the company acquired theatrical distributor Freestyle Releasing, renaming it Entertainment Studios Motion Pictures. The imprint produced and distributed films such as shark thriller 47 Meters Down, the highest-grossing independent film of 2017, and Chappaquiddick, about former senator Ted Kennedy’s infamous car accident.

Allen with his wife Jennifer Lucas in 2018, at the Entertainment Studios Oscar Gala benefiting Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

Major studios have largely abandoned the mid-budget, script-driven movie that was the building block of Hollywood for so long, choosing to focus on blockbuster franchise films (often featuring superheroes) and leaving the rest to streaming services like Netflix. That’s where Allen sees an opportunity.

“If you manage the numbers correctly, there’s a good business there of movies that do $40M to $60M at the box office,” he says. “$40M is a disaster for studios, but a success for us.”

But Allen’s biggest purchase yet has nothing to do with movie stars. In March 2018 he paid $310M to a private equity consortium for the TV assets of one of America’s most trusted names: The Weather Channel. (IBM separately owns The Weather Channel’s forecasting technology and the weather.com website.)

Allen describes the channel as an undervalued asset, akin to a great house in a great neighborhood owned by a couple in an acrimonious divorce. And since acquiring it, ratings have hit their highest numbers since 2012, ad sales are up, and the channel is getting ready to launch a Spanish-language version: The Weather Channel en Español.

It also doesn’t hurt that having The Weather Channel in its portfolio can give Entertainment Studios more leverage over distributors as it looks to get carriage for its other channels—an old trick used by the big media companies. (Your pay-TV provider only carries Nat Geo Wild because it wants Fox News.)

A Different Model

Allen can make producing content that’s too small for major studios highly profitable for Entertainment Studios because he knows how to be efficient with resources. That’s out of necessity. For many years, he was unable to secure investors or bank financing, having to bootstrap his business by using factor firms to finance his accounts receivable—at interest rates approaching 26% for the first 15 years of the company. This despite the fact that Allen says he’s failed to collect just $30,000 out of more than $500M in receivables over his career. So, he’s been forced to find ways to do things creatively.

For example, Allen was flabbergasted by the high cost of renting trailers for talent. He decided to buy his own, sight unseen, saving hundreds of thousands of dollars a year by owning and depreciating an asset rather than paying rent.

And as Hollywood is forced to trim some of its largesse, Allen believes his early struggles give him an advantage.

“I had to be efficient in order to survive day one,” he says. “They’re learning to become efficient to survive, and it’s easier to be born efficient than it is to try to become efficient.”

Entertainment Studios is different from its competitors in another notable way: Its people stick around. In show business, where high employee turnover is common, that makes Allen an outlier. And he says, a key to his success.

“Strong championship sports teams have very little turnover,” he says. “Because you lock in and you get to know each other.”

Speaking of sports, one of Allen’s biggest recent moves was teaming up with Sinclair to acquire Fox’s former regional sports networks from the Walt Disney Company.

The acquisition comes at a time when Americans are increasingly moving away from pricey cable and satellite packages, causing national and regional sports networks to lose subscribers and putting pressure on them despite relatively high ratings. Allen sees it a little differently—he believes sports are so valuable because TV needs them to survive.

Behind the scenes at the Weather Channel, which Allen purchased for $300M.

“There are two reasons television is alive: localism and sports,” he says. “If we lose sports, that will be a big problem for broadcast television.”

The Next Stage

Allen has spent much of the last two decades on a consistent winning streak. But he’s about to face off against the country’s largest cable company in the land’s highest court.

On November 13, the Supreme Court will hear arguments in the $20B suit Allen filed against Comcast Corporation. (He filed a separate, $10B suit against Charter Communications, but the Supreme Court decision will resolve both). Allen says the genesis of this came from a discussion with Obama administration officials, who asked him whether Comcast and other cable giants were good corporate citizens.

“I said, ‘Hell no,’” Allen says.

His argument was that cable and satellite industries spend $70B a year licensing cable networks, and not one cent goes to African-American-owned media. That lack of inclusion did not seem to align with good corporate citizenship, at least to Allen. He agreed to lead an effort to change that, but wanted to do things his way.

Allen decided to file his lawsuits, and he also named the NAACP, the Urban League, and Al Sharpton, accusing them of providing cover to these organizations and being complicit in “hurting the black community because of token donations from Comcast,” Allen says.

Both cases ended up in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which agreed with Allen, deciding that race was a factor in the cable company’s decision not to carry Entertainment Studios’ programming. Allen says the Supreme Court went along with most of the Ninth Circuit’s decision—but, of course, that would have been too easy.

“Comcast got the Supreme Court to look at the law I used, the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Section 1981—which was put on the books to protect the newly freed slaves, to make sure we had a pathway to economic inclusion,” he says. “It’s the very first civil rights statute in the United States.”

With his wife and children at the premier of 47 Meters Down in 2017.

The Department of Justice filed an amicus brief on August 15 that looks to more narrowly redefine the Reconstruction-era statute on which Allen is basing his claim. In what will be an historic event, Department of Justice lawyers will actually be standing in the court helping argue the case on behalf of Comcast. If the Supreme Court were to follow the department’s new interpretation, Allen would have to prove that race was the sole reason—not merely a factor—behind Comcast’s decision not to carry his content.

That’s an impossible standard, he says.

“They can actually say, ‘Byron, I’m discriminating against you—99 percent of the reason is because you’re black and 1 percent because you’re wearing tennis shoes,’” Allen says. “And you cannot use this law. The biggest reason why I am working vigorously to protect this civil rights statute in the Supreme Court is because I want to make sure we have economic inclusion for all Americans, especially African-Americans, the furthest left behind.”

But as he approaches his biggest stage yet, Allen remains calm. He’s no stranger to bright lights. Besides, he has the ultimate business superpower: He’s a comedian.

“I think comedians make excellent business people because we look at things differently and we figure out what’s not there and how to put it there. We figure out what can be adjusted and how we can adjust it to get it on the right track,” he says. “I’m standing in front of a crowd of 18,000 people with a microphone and a spotlight and I have to tell people to listen to me for an hour and go along with the thoughts that I’m putting in front of them. It’s the ultimate sales training.”