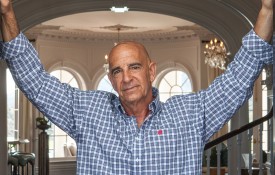

Growing up in Northern Iowa, Nancy Aossey could not have imagined she would one day be sitting face-to-face with a notorious African warlord in his secret hideout. But it’s all in a day’s work for the president and chief executive of International Medical Corps (IMC), one of the world’s biggest humanitarian organizations.

Staffed with 7,500 aid workers, doctors, and nurses, IMC, based in Los Angeles, has delivered more than $2.8B in assistance and trained tens of millions of people in 80 countries. With a focus on health care, the organization operates in war zones and countries facing famine and disease in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas. It’s also there when natural disasters cause destruction across the globe or in the United States.

Need-Based Growth

Former First Lady Michelle Obama summed it up perfectly when she praised Aossey during a 2011 commencement address at the University of Northern Iowa, Aossey’s alma mater, telling the crowd, “She took over, and IMC took off.”

The key to the organization’s tremendous growth, Aossey explains, has been IMC’s singular focus on working where there is need and building sustainable, local solutions. “What’s happening in the world right now?” and “Are we there?” are pressing questions that drive her.

IMC was founded in 1984 by Dr. Bob Simon, a renowned expert in emergency medicine, after he returned from Afghanistan, where he learned that doctors were being killed and detained as war with the invading Soviet army raged. Two years later, Simon, now IMC’s chairman, hired Aossey as CEO. With only three employees and funding from Simon’s own resources combined with funds from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the scrappy startup was on its way to creating a new model for humanitarian work. Former President Reagan endorsed IMC’s early efforts in Afghanistan, and former President Obama later highlighted its work to end the West Africa Ebola outbreak during his State of the Union.

For Aossey and her staff, recent responses include a wide range of deployments, from providing doctors, nurses, medicine, and power generators in Puerto Rico after the 2017 hurricane and supplying medical care, mental health services, and hygiene kits to Syrian refugees, to working in Rwanda during the civil war and genocide. Searching for hospitals and homes to work from where massacres hadn’t taken place was among the numerous challenges Aossey faced as neighbors killed neighbors and churches became death traps.

“We could hear the screams at night. All the relief workers that were there slept in the same room because we didn’t want to be alone,” Aossey says.

Providing relief after the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004 (Photo Credit: IMC)

Humble Roots

Recalling her modest upbringing in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Aossey says her father, a retired milkman, and her mother, a stay-at-home mom turned secretary, encouraged her to give back. “They have a real heart and tremendous empathy for other people,” she says.

Aossey’s father sometimes gave free chocolate milk to neighborhood kids who couldn’t afford it and gave up part of his delivery territory to help a co-worker struggling to support his family.

Neither of her parents attended college, but were adamant that she get a four-year degree. Years later, receiving an honorary doctorate from her alma mater, was an emotional day, she says. A student who had survived the genocide in Rwanda spoke and Aossey’s parents attended the ceremony.

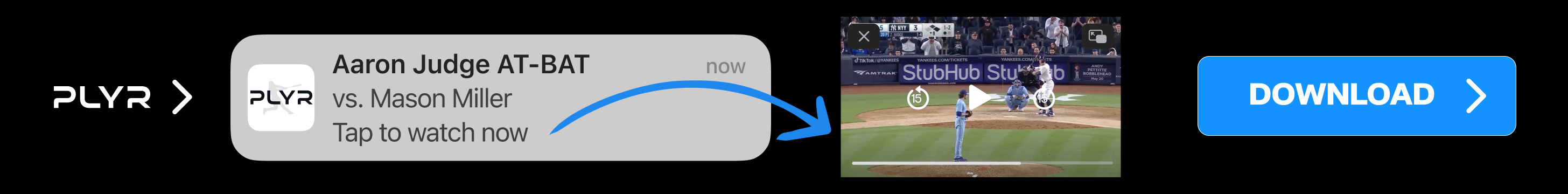

Embracing Technology

Typically, Aossey is up at 4 a.m. on her iPad getting updates from her teams overseas and checking international news. When she arrives at the Santa Monica office, where pictures of IMC in the field line the walls, she’s ready to manage a remote and widely distributed team. “We’re a 24/7 worldwide operation,” she says. “Using technology has also meant less travel.”

Many meetings are conducted on Skype. IMC was an early adopter of new technologies, where connectivity can mean the difference between life and death. During relief efforts for 2010 earthquake in Haiti, IMC used Twitter for the first time, as well as Facebook, to share information with news media and other organizations. Instagram and YouTube are also essential to raising awareness, whether on a specific crisis or for overall marketing.

Extreme Logistics

It’s not unusual for IMC to be on the ground within days or even hours of a disaster, often the first to arrive. The organization is known for its ability to use its highly developed assessment methodology and focus on logistics. For example, successful supply chains are essential.

“We’ve partnered with organizations that have vaccines, but they might not be able to maintain the integrity of the cold chain to keep the vaccine at the right temperature,” Aossey says. “We view our work through the lens of problem solvers. We’re willing to look for gaps.”

IMC devised a cold chain for the transport of vaccines after its first mission in Afghanistan. At the same time, it created an intensive training program for medics and worked with locals to organize vaccination efforts. After a few years, Aossey realized they had a workable formula. “If you can be effective in Afghanistan, you’d probably be effective anywhere,” she says.

Fighting the ‘Nurse Killer’

In 2014, with $5M from USAID, IMC set up a treatment unit in Liberia to stop an outbreak of Ebola, known as the “nurse killer.” “We had to protect healthcare workers because, although they want to help, if there’s a 50% chance they’ll die, they will stay home,” Aossey explains.

Nancy Aossey holds an infant in the aftermath of the 2010 Haiti earthquake (Photo Credit: IMC)

As the deadly disease grew exponentially, IMC erected Ebola treatments centers, which cost $1M per month to run. In addition, the organization launched a program to train 5,000 health workers who could treat the deadly disease.

Currently, IMC staff members are in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where a new outbreak of Ebola threatens to be as deadly as the 2014 outbreak. In collaboration with FedEx, IMC has set up portable units to assist in the response. As in Liberia, IMC personnel in DRC have to worry about contracting Ebola themselves. But, the DRC presents new challenges: militia fighting that wasn’t present in Liberia. Security concerns create a more complex and costly response, causing IMC to scale up its security protocols.

Danger Zones

No other outside organizations were willing to risk working in Angola during the civil war in 1990, when IMC arrived to address the highest infant mortality in the world by administering lifesaving vaccinations. Rebel leader Jonas Savimbi controlled the territory. He requested to meet with Aossey and her USAID colleagues, summoning them to his compound deep in the African bush. Blindfolded, they were driven to his underground bunker.

“It was surreal. I mean, how are you supposed to trust in that moment?” she says. “I didn’t feel our personal security was at risk because he agreed to meet with us.”

Because Savimbi was a military man, he addressed Aossey first since she held the highest title. “I told him we didn’t need anything from them, just to be left alone and to get assurances that his army wouldn’t target us,” Aossey says. “He was charming. And he was a murderous war criminal.”

With Savimbi’s promise, IMC partnered with a loose-knit group of women in villages who took care of health needs. Ultimately, IMC administered 160,000 vaccinations.

Despite many successful responses, IMC has lost staff members, in countries including Afghanistan, Bosnia, and South Sudan.

Harnessing the Power of Hollywood

Fighting disease in war zones is a stark contrast to the glamorous part of Aossey’s job, which entails mingling with celebrity supporters like Sienna Miller, a global ambassador for the organization since 2009. Actresses Robin Wright and Sanaa Lathan also serve as global ambassadors, helping disseminate IMC’s message to Hollywood and beyond. IMC’s powerhouse board of directors, advisory board, and leadership council, including director/producer J.J. Abrams, spearhead bringing in what Aossey calls the “flexible funds” that are so vital. “The flexible dollar is always the most important dollar to an emergency group,” she says.

As one of the world’s most esteemed female social entrepreneurs, Aossey has been honored with numerous awards, including the Goldman Sachs 100 Most Intriguing Entrepreneurs, and the Young Presidents’ Organization Global Humanitarian Award.

“The awards are our achievements, not my achievements. They go to IMC and all the unsung heroes,” Aossey says.