As a child living in Hungary, Steven F. Udvar-Házy has vivid memories of sitting in his first-grade classroom. It was the early 1950s, and Hungary had become a satellite state of the Soviet Union following World War II. Students wore identical white shirts with red neckerchiefs, the requisite uniform for school children in communist-ruled countries.

Surveying the classroom, young Steven saw no trace of Hungarian history or culture. Instead, staring down from pictures hung high on the walls were the stern faces of Vladimir Lenin and Josef Stalin. Daily lessons were supplemented with lectures – sometimes as long as 90 minutes as he recalls – steeped in propaganda, extolling the virtues of socialism and communism while demonizing the West.

“We had to sit there … with our hands behind our backs,” Házy recalls with calm vexation. “Listening to this constant brainwashing about how terrible the West was.”

Fortunately, there would soon be a break in this oppressive cloud cover of indoctrination, providing a respite of wonder that would propel a boy’s journey to a place of possibilities and, eventually to becoming the visionary creator of an emerging industry.

There was an airshow happening at a small airport just outside of Budapest, and Házy’s father got tickets. It was a transformational experience. “[What] those planes represented, the fact that they could just take off, was, for a child, synonymous with freedom,” says Házy. “From that moment on, aviation became my passion.”

A Harrowing Escape

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956, a two-week uprising that brought about the collapse of the Soviet-led government, was a foreboding sign of more strife to come. As a new Soviet-backed regime re-established its grip on the country, the opportunity to flee presented itself. In the winter of 1958, after a couple false starts due to harsh weather, Házy and his family made it across the border, braving minefields, barbed wire, and lookout towers between heavy snowstorms. They eventually took refuge in Sweden.

[What] those planes represented, the fact that they could just take off, was, for a child, synonymous with freedom. From that moment on, aviation became my passion.

Házy’s father had a sister who had already successfully made it to New York City from Hungary. Within six months, the family obtained green cards and visas to emigrate to the United States. Házy arrived in New York with an English vocabulary that consisted of two words: “yes” and “okay.” He got into a fair share of fights at school, battling to hold his own against the tough children who saw him only as an immigrant outsider who notably didn’t play baseball.

He was getting good grades in spite of the harassment, but his parents transferred him to a small parochial school on the west side of Manhattan. Házy credits the strict and sometimes intimidating Catholic nuns at Holy Trinity with helping to guide and stabilize his transition into American culture and customs.

Having left all wealth and possessions behind in Hungary, the entire family endured a brief period of starting over. As his father had developed health problems that affected his ability to work, it was left to Házy’s mother, who worked for acclaimed fashion designer Pauline Trigère, to support the family.

After school, at least twice a week by his recollection, Házy would take any combination of subways, buses, or cabs to LaGuardia or Idlewild (now JFK) airports to marvel at the activity. Talking his way into control towers, hangars—anywhere to be near the action—Házy would log information about the types of aircraft that different airlines flew, flight patterns, destination cities, and anything else related to air travel.

When Házy’s brother, four years his senior, landed a scholarship to study science at UCLA, another move was eminent. The balmy climate and relaxed pace proved too alluring to resist, and the family soon relocated to Los Angeles.

Earning his pilot’s license at the age of 17, Házy adjusted nicely to the Southern California lifestyle. After graduating from University High School, he followed in his brother’s footsteps and attended UCLA, working as a lifeguard during the summers at Manhattan Beach, Redondo Beach, and Zuma Beach.

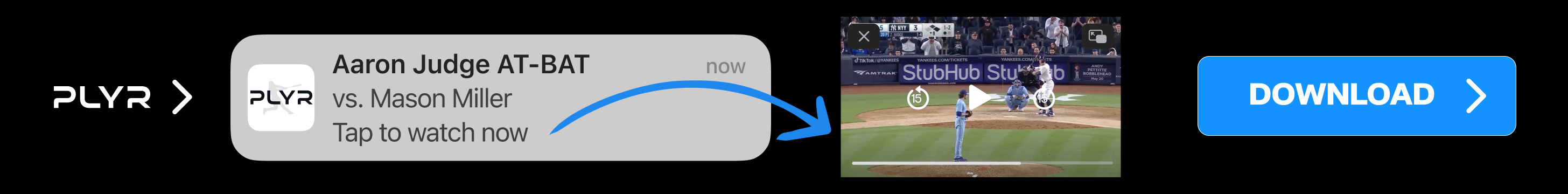

Opening Celebration of Air Lease Corporation on the NYSE, April 20th, 2011

“It was a great job,” reminisces Házy. “The starting pay was $2.04 an hour.” He and his brother would drive the 1956 black Oldsmobile convertible with red interior that they shared. One dollar would buy them four gallons of gas, enough for a few round-trips to the beach.

Taxiing the Runway

While still in college, the young entrepreneur brokered an international deal that elevated his confidence. He learned that Air New Zealand had a 90-seat Lockheed Electra that it wanted to sell so it could upgrade to a new, four-engine, 150-seat Douglas DC-8 and begin offering flights to Los Angeles.

“I found an airline in Alaska that wanted to buy that plane,” recounts Házy. “[Air New Zealand] wanted $1M. I said, ‘Will you pay me $50,000 if I have a buyer?’ They said, ‘Sure, come down.’ I had sent telegrams, so when I showed up with the pilot, they said, ‘Who is this kid?’ They had no idea I was just 21. That gave me confidence that this thing is doable.”

After graduating from UCLA, Házy wasted no time in pursuing his dream to start his own airline. Identifying a potentially lucrative market along the coast of California catering to Vandenberg Air Force Base in Santa Barbara County, he lined up investors and started Astro Air, a small commuter airline that hoped to connect Los Angeles and the Bay Area via Central California.

His idea to start a regional carrier was ahead of the curve, but the numbers didn’t add up. “My projections on cost were too low and my optimistic projections on sales were too high,” he says. “So you can figure out what happened.” The company lost money (“postgraduate tuition,” Házy calls it), but the experience provided valuable insight that would fuel his next bold move.

Házy realized he was paying the same monthly fee to lease his airplanes, regardless of the number of passengers on board. “The lessor was getting paid, no matter what. I said to myself, that’s a better business model [owning the airplane].”

A second observation Házy made was to note the relationship between economics and developing technology. As the airline industry transitioned from propeller planes into the jet age in the 1970s, the cost of a typical airplane increased by up to five times, making ownership a prohibitively expensive venture for a growing number of airlines, particularly outside the U.S.

“My whole idea was, if we could bring the latest, best airplanes to these airlines all over the world through the medium of leasing, they could be just as good as a U.S. airline, or an Air France, or a British Airways,” reasons Házy. “We [could be] a tool—a medium—for those airlines to modernize their fleets.”

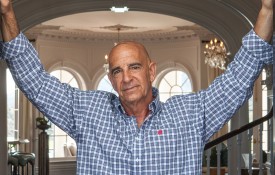

Udvar-Házy in the middle of a discussion

Taking Flight

Now just 26 years old, Házy heard that Aeroméxico was starting a new service from LAX to Acapulco, and the airline needed a Douglas DC-8 for the route. National Airlines in Florida had a used one for sale; the price tag was $2.2M. Házy and two business partners chipped in $50,000 each and arranged a meeting with Aeroméxico.

Lacking the funds or government approval to purchase the plane outright, Aeroméxico agreed to put up three months’ rent, plus a $150,000 security deposit, which would be returned at the end of the lease. Házy and his partners then approached several different financial institutions in search of a loan. They were rejected for a variety of reasons: lack of experience, the untested nature of the business model, the liability factors involved—even the unlikely event of a government coup d’etat.

Finally, one bank saw a spark of ambition that shone through the relative youth and lack of experience. United California Bank offered that if Házy could get the Mexican government to guarantee all the lease payments, the loan could be approved. A last-minute meeting was arranged with a representative from the Mexican government so the partners could pitch the idea. Bolstered by Aeroméxico’s advance payment and security deposit, the deal was summarily signed, notarized, and embossed with a wax seal that same evening. Házy was able to return to the bank the following day with the requisite government assurances.

“That was the beginning of aircraft leasing,” he says. “Once we established ourselves, we could at least get some financing as long as we put our own money in the deal.” International Lease Finance Corporation (ILFC) was born.

Within a year, Házy also got involved with SkyWest, Inc., the largest regional airline in North America. He continues to serve as a longtime director for the carrier, which has grown from 3 airplanes to more than 700 and operates flights for Delta, United, Alaska, and American Airlines and now serves more cities in the U.S. than any other airline.

Air Lease Corporation was founded in 2010

Stratospheric Growth Model

Soon after its inception in 1973, ILFC quickly became the world’s largest aircraft lessor by value, leasing Boeing and Airbus to major airlines worldwide. Airplane leasing was similar to renting real estate, Házy points out, in the sense that income generated from one deal was often used to leverage the next. Returns are more rapid than in real estate, but so is depreciation, as the average lifespan of an airplane is approximately 25 years.

“The idea is to have 100 percent utilization,” says Házy. “Our business is long-term leases, anywhere from 8 to 14 years. There is no idle inventory.” ILFC provides the plane, and the airline covers the cost of maintenance, fuel, crews, insurance, and everything else. Airlines pay a fixed amount every month, whether a plane is flying every day or spends a week in maintenance.

As the world becomes more connected, Házy says, air travel for business and leisure is becoming more accessible to the world’s population. “Mobility is becoming part of today’s youth culture,” he says, pointing out that off-season flight deals from LAX to Europe can be scored for $150, less expensive than a week’s worth of parking at LAX.

“In the mid-1950s, you had maybe 20 million one-way passengers a year in the world,” Házy explains. “As the middle classes grow [worldwide], the potential for air travel is unbelievable. The number of people flying is growing faster than population or GDP around the world. This year, we’re projecting more than 4 billion [one-way] passengers. The U.S. will make up 25 percent of that.”

Between increased air travel and the need to replenish aging fleets, the demand is evergreen, at least until teleportation becomes a viable option. “There are 24,000 Western-built jet airliners, with more than 100 seats, flying in the world,” says Házy. “So you figure that 700 to 800 of those need to be replaced every year—even if there’s no growth.”

ILFC grew into a $35B company with 180 employees. Operations were lean because operation of the asset was not part of the equation. “Of all public companies, we had highest earnings and assets per employee in the U.S.,” he says. “We got trophies left and right.”

Steven F. Udvar-Házy hangar at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum companion center in Chantilly, VA

New Ventures, Familiar Patterns

It’s a model he would follow in his next venture. Házy served as ILFC’s founding chairman and CEO through AIG’s $1.4B acquisition in 1990, on up until he “retired” in January 2010.

Within weeks, he formed Air Lease Corporation (ALC; NYSE: AL) with John Plueger, ILFC’s former chief operating officer. The company has upwards of 85 employees, many of whom, like Plueger, share a decades-long association with Házy. “Having the familiarity of an experienced team working together has really accelerated our ability to move forward.”

Plueger offers the following perspective on the man he has worked alongside for more than three decades: “He’s a tough, brilliant negotiator. Everything I have ever learned in this business is from Steve. He has been much much more than a mentor to me, and to others. We’ve shared our professional and family lives for 32 years. Our personal relationship reflects our common bond of aviation and our industry. Truthfully, we talk of little else.”

At the end of 2017, ALC owned 244 aircraft and managed an additional 50, serving 91 airline customers in 55 countries. With assets listed at more than $15B, the company reported more than $1.5B in total revenue in 2016. Plus, ALC has almost 400 new jets on order from Airbus and Boeing.

“We’re growing, but if growth happens too quickly, you can’t manage it,” cautions the billionaire businessman, who turns 72 this year. “There’s a size at which the culture changes. What works for 90 or 100 people won’t necessarily work for bigger companies.”

In terms of his legacy, Házy prefers to shift the focus to the new generation in which he hopes to inspire the same fascination with flight that he experienced while growing up. “I think travel is a form of education,” he says, adding, “and the airline industry has transformed the planet in the last 60 to 70 years.”

The number of people flying is growing faster than population or GDP around the world. This year, we’re projecting more than 4 billion [one-way] passengers. The U.S. will make up 25 percent of that.

In 2003, the Steven F. Udvar-Házy Center, a companion facility to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., opened in Chantilly, Virginia. The building holds more than 290 air and space artifacts, including the Enola Gay and Space Shuttle Enterprise.

“I’m very proud of the center because of the opportunity it gives children to see the history of aviation,” says Házy. “If I can have children have that same feeling I had when I was a six-year-old at the airshow in a communist country, that to me is worthwhile.”

Over the years, Házy and his wife, Christine, have also donated more than $100M to Stanford University and the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Arizona. The married couple has four grown children. One son works in the aviation industry for a “friendly competitor” of ALC, offers Házy.

Into The Small New World

Házy still pilots his Gulfstream G650 and G500, which are parked at the ALC private hangar at Van Nuys Airport, whenever the opportunity presents itself. Lauding the advancements in design and safety that have made air travel in the U.S. increasingly safe and incident-free (notwithstanding the occasional kerfuffle inside the cabin that goes viral on social media), Házy notes that there were no U.S. air fatalities on commercial airlines in 2017.

In addition to his own insatiable hunger for knowledge, Házy credits the mentors who helped him gain a foothold in the industry back in the Golden Age of Aviation. He counts Bob Six, CEO of Continental Airlines from 1936 to 1980, and Herb Kelleher, co-founder and former CEO of Southwest Airlines, as indispensable mentors who facilitated his professional development with their sage personal advice and bold business moves.

“I’m still fascinated by the industry, although it moves at a faster pace,” says Házy. “Now we’re in a much more mature business.” As a greater percentage of the world’s population embraces the opportunity to travel by air, a new Global Age of Aviation is taking off. And there may be no one better positioned than Steven Udvar-Házy to ensure peak altitude is achieved.