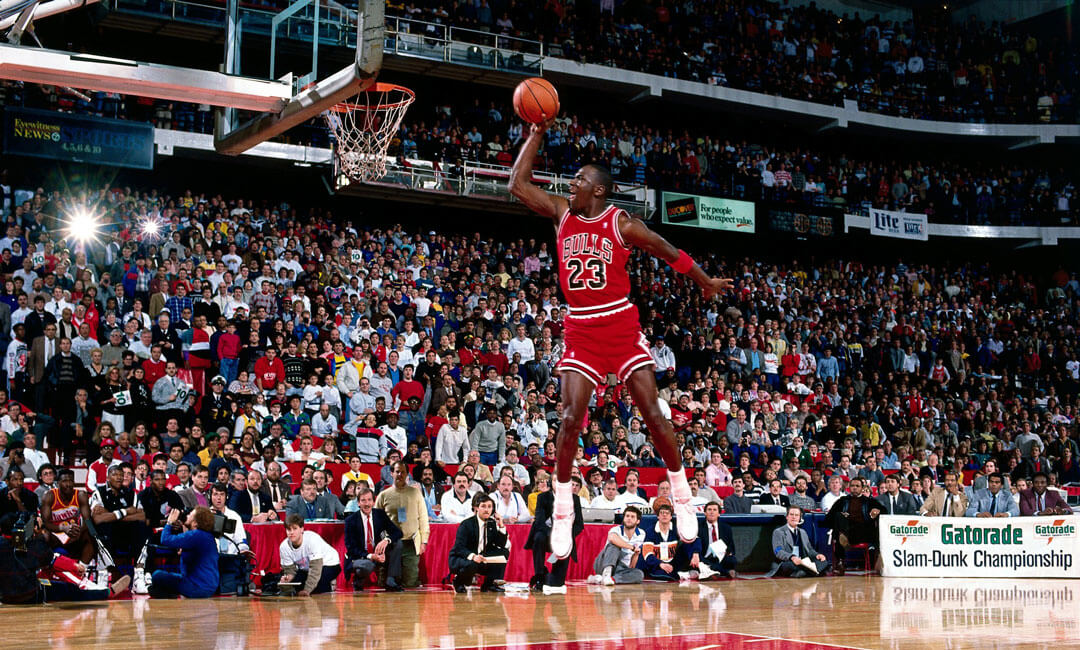

Michael Jordan needs no introduction. Something of a legend for turning failure into success, he is the author of the longest quote on my company’s failure wall — which was tricky to paint but worth the extra effort:

I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times, I’ve been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.

Most of us don’t fail or succeed in the glare of a national spotlight, much less do it thousands of times, with analysts endlessly critiquing every move. Perhaps that’s why people love sports: they provide a black and white analogy for the gray backdrop of life. The ball is in or it’s out, the basket is made or missed, the game is won or lost. Watching our favorite stars pull through when the chips are down inspires us to do the same in our own lives. And no one has inspired more sports fans, young and old alike, than Michael Jordan.

The story of Michael Jordan not making his high school team has been told and retold, but continues to inspire with each retelling. In 1978, sophomore Michael Jordan tried out for the varsity basketball team at Laney High School. When the list was posted, Jordan’s name wasn’t on it. Instead, he was asked to play on the junior varsity team.

The reasoning behind the choice wasn’t that Jordan didn’t have enough talent or hadn’t already distinguished himself as an outstanding basketball player. Rather, it came down to seniority, size, and a strategic decision: The varsity team already had eleven seniors and three juniors. That left space for only one more player, and the coaches chose another sophomore, Jordan’s friend Leroy Smith. Smith was not as good as Jordan but he added size to the team, as he was 6’6” compared to Jordan’s diminutive 5’10”. What’s more, the coaches knew that if Jordan had been chosen for the varsity team, he would play only when needed as a substitute for the more senior varsity players. On the junior varsity team he would get more playing time and a chance to truly develop.

It was a perfectly logical choice for the coaches to assign Jordan to the junior varsity team for his sophomore year. But 15-year-old Jordan was devastated when the list was posted without his name. In his mind, it was the ultimate defeat, the ultimate failure. “I went to my room and I closed the door and I cried. For a while I couldn’t stop. Even though there was no one else home at the time, I kept the door shut. It was important to me that no one hear me or see me.” Jordan was heartbroken and ready to give up the sport altogether until his mother convinced him otherwise.

“His relentless drive would lead him to break numerous records and become the most decorated player in the history of the NBA…he’s credited with dramatically increasing the popularity of basketball both in the United States and internationally, and inspiring the next generation of basketball players…”

After picking himself up off the floor, Jordan did what champions do. He let his failure and disappointment drive him to be better. He played on the junior varsity team, and he worked himself to the limit. “Whenever I was working out and got tired and figured I ought to stop, I’d close my eyes and see that list in the locker room without my name on it, and that usually got me going again.”

It became a pattern throughout Jordan’s life that a disappointment or setback resulted in a redoubling of effort. High school rival player Kenny Gattison, who led his team to beat Jordan’s team for the high school state championship, put it this way: “You got to understand what fuels that guy, what makes him great. For most people the pain of loss is temporary. [Jordan] took that loss and held on to it. It’s a part of what made him.”

For most people, public failure becomes public humiliation, and that leads to retreat. Fear of public speaking is a good example. Few people are psychologically afraid of speaking their mind and even fewer have physical speech impediments preventing them from doing so. Yet glossophobia, the technical term for speech anxiety, is consistently ranked among the most prevalent mental disorders, with a reputed 75% of the world’s population experiencing some degree of anxiety around public speaking. Our fears have little to do with speaking, of course, and far more to do with the perceived impact and reaction that our audience may have. But for Jordan and elite performers like him, the fear of failure and public ridicule is transformed into a drive for success.

The pattern of defeat followed by success would follow Jordan to the University of North Carolina and later to the NBA. His relentless drive would lead him to break numerous records and become the most decorated player in the history of the NBA. What’s more, he’s credited with dramatically increasing the popularity of basketball both in the United States and internationally, and inspiring the next generation of basketball players including Lebron James, Dwyane Wade, and Kobe Bryant. You can’t think of the word “champion” without thinking of Michael Jordan, and there’s no better proof that failure is simply a stepping stone to success.

Michael Jordan faced another formidable challenge decades later, when he became the owner of the NBA basketball franchise, the Charlotte Bobcats. Jordan had been a minority owner since 2006 but bought the majority stake from Bob Johnson in 2010. At the time, the business was hemorrhaging, so Jordan used his own money to cover the significant operating losses the team was experiencing.

The first season was lackluster but things got worse. In the 2011-2012 season, the team earned a mere 7 wins alongside 59 losses – the worst record of any team ever in the history of the NBA.

In addition to—or maybe because of—their disastrous record, the Bobcats had poor community support. The Bobcats brand was synonymous with disappointment, despite having one of the best basketball brands of all time at the helm—Michael Jordan himself.

But after the 2012-2013 season came to a close, Jordan started to turn things around. First, he brought in former Lakers assistant coach Steve Clifford to replace Mike Dunlap. In a change every bit as important as the new coach, Jordan agreed to remove himself from the process of managing the team’s operations.

Instead, Jordan focused on what Jordan can do better than anyone else: revitalizing the brand. He applied for and received permission to change the team name to the Charlotte Hornets. Jordan himself became more involved in community events and forged a connection between the team and the city.

The changes paid off. The team finished the 2013-2014 season with a winning record of 43-39, the second best year in the history of the franchise. They even made it to the playoffs. At the same time, ticket and merchandise sales skyrocketed and public opinion improved dramatically. The team was well on its way to making both a comeback and a profit.

Most of us look to successful people and assume they can do anything because of their past successes. The old joke about asking your doctor for stock tips comes to mind, as if just because you can cure an illness, you have wisdom about everything. Doctors don’t make great stockbrokers, brain surgeons are horrible rocket scientists, CEOs aren’t usually exceptional cooks, and basketball stars are rarely great baseball players (you can ask Jordan about that last one as well). Experience and knowledge are only valuable where applicable.

This mindset doesn’t just fog our external lenses, it also blurs how we see ourselves. It is often hard for successful people to admit that they won’t be good at something new. In Jordan’s case, his basketball skills didn’t translate into basketball management. It took some time, but Jordan certainly deserves credit for acknowledging what wasn’t working and trying new things until he hit on a winning combination. He gave up managing and focused on marketing, a skill he was uniquely qualified for. For Jordan, that became the recipe for success:

It’s harder than most people think. Some people have been in this business a lot longer and still haven’t put together a sustainable, successful scenario. When you make bad decisions, you learn from that and move forward. I think I’m better in that sense. I’ve experienced all of the different valleys and lows about ownership and the success of businesses. Does that constitute me being a better owner? Then I guess I am.

Hard, yes, but flexing a new muscle is also exhilarating, especially when you eventually succeed. As Jordan puts it, “…it’s been fun. It’s been hard, but I’ve had fun doing it.”

[For more of Jeff Stibel’s Profiles in Failure articles, click here]