When Michael Pirovolakis was around 2 years old, he was diagnosed with spastic paraplegia type 50 (SPG50). Doctors didn’t know much about the disease, but they advised Terry and Georgia that their son would be paralyzed from the waist down by age 10 and quadriplegic by 20. Michael would never talk or walk and might deal with regular seizures. The devastation was unimaginable, and the two terrified parents went home with the doctor’s guidance to love their son and give him the best life possible because there was nothing that could be done.

After two days of crying, the couple decided that they were going to change Michael’s story. “We realized we had two options: love and support our child or love and support our child while finding him a cure,” Terry said. He and Georgia knew it would take time, money, and everything in between, but their commitment to finding a cure didn’t waver.

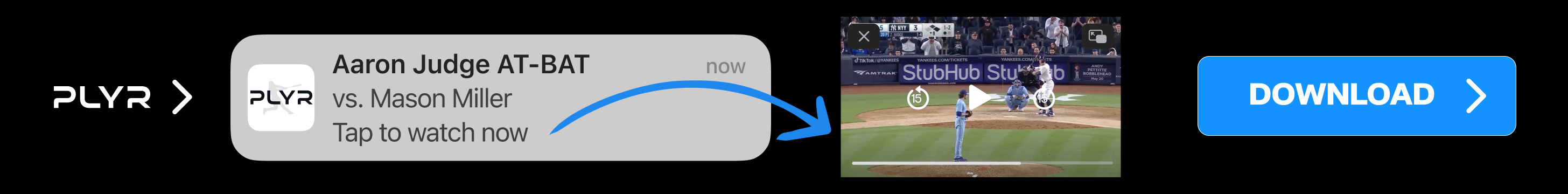

Terry and his son Michael. Credit: SickKids Ontario, Canada.

NOT TAKING ‘NO’ FOR AN ANSWER

A natural researcher and very resourceful person, Terry poured his grief and fear into action. He began researching, staying up all hours of the night to pore over articles, clinical trials, and medical journals from the workstation in his bedroom closet. His research pointed to gene therapy as the path to pursue, and even the $4 million needed to create a drug for Michael didn’t slow his momentum.

After liquidating their life savings and filing an application with Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) to become a charity, Terry and Georgia started making calls to convince a lab to engineer a mouse. The two items that take the longest in gene therapy are growing the cells to test the therapy and breeding a colony of mice. “I knew it could take up to 18 months for the mice, so I called Dr. Lutz at the Jackson Laboratory in Maine,” Terry says. “I cried on the phone with her, begging her to make a mouse for my son’s condition.”

Getting Dr. Lutz to handle the mouse was only the beginning. Next, Terry had to convince a gene therapist to actually design and create the therapy. Without much of a plan, he purchased a ticket to a cell and gene therapy conference in Washington, D.C. There, he talked to experts, got confirmation that gene therapy was the best path, and asked everyone he talked to who was the best person to help with this endeavor. “Ninety percent of the people I talked to recommended Dr. Stephen Gray,” Terry says.

It just so happened that Dr. Gray was receiving an award at the conference, and as soon as he stepped off the stage, Terry was waiting. After hearing his pitch, Dr. Gray was hesitant. He didn’t have the resources or bandwidth to take on another project, but with the desperation and determination of a father fighting for his son’s life, Terry persisted. “I wouldn’t take no for an answer,” he says. “Eventually, Dr. Gray agreed to help.”

FROM TESTING TO TREATMENT

Using a virus called adeno-associated virus, Dr. Gray began creating a gene therapy to treat, and possibly cure, SPG50. The drug, which is injected into the spinal column, enters the brain and brain cells, drops the gene, and creates the missing protein, allowing the brain to function properly.

After the therapy was successfully completed, it was time for testing. Dr. Gray tested the treatment in the cells, injected it into animals, and monitored the results for months. For Michael, every additional day that it took to get the treatment approved, his condition worsened.

“At this time, Michael was about two-and-a-half years of age, he was in the negative third percentile for head growth, and his feet were getting paralyzed,” Terry says.

Because of the time implications, every day felt like a race for the family and everyone they had brought together to work on this therapy. Getting the news that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Health Canada wanted further testing in animals was a setback, but in true Terry fashion, he continued pushing forward. “We tested in rats, then nonhuman primates, which were very hard to get during COVID,” he says.

Eventually, the SPG50 gene therapy was given the green light for manufacturing. A clinical batch of the drug was manufactured in Spain, then sent back to the U.S. and Canada at the end of 2021. In March of 2022, just under three years from the day Terry and Georgia got the news about Michael’s disease, Michael was treated with the gene therapy.

Dr. Manohar-Shroff, Dr. Farrukh-Munshey, and Dr. Jim-Dowling

JUST THE BEGINNING

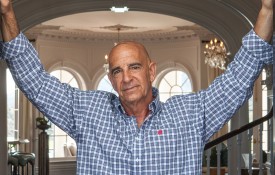

Terry didn’t have a background in the medical field. In fact, most of his career was spent setting up complex call centers and other technical environments. But his abilities to bring people together, coordinate complex problems, and work through the unknown were all skills he relied on to make the impossible possible. After crossing the finish line for his son, many people expected Terry to step back and rest, but he was just getting started.

Within 90 days of treating Michael, Terry opened a clinical trial in the US. Three children in the US and two Spanish teens had all received the same treatment to date. With those results in hand, Terry and the team went to the FDA to ask for a phase three clinical trial. Just this summer, the trial was approved to move forward.

“Very early on, Dr. Gray told me, ‘I don’t make therapies for just one person,’ and I agreed,” Terry says. “I wanted to treat Michael, but I also wanted to eradicate SPG50 and other rare diseases.”

To him, the disease was the enemy, and he wanted revenge for what it had done not only to his own family but other families around the world.

To make the therapy accessible to more children, the team recognized a significant need for additional resources. They pursued grants, reached out to venture capital firms, and left no avenue unexplored in their quest to fund not only SPG50 but other stalled programs in need of support.

“I wouldn’t take ‘no’ for an answer,” Terry recalls. His focus wasn’t on profit or licensing but on saving more children. To secure the resources needed to scale, he established his own organization, Elpida Therapeutics, and built partnerships with the Columbus Children’s Foundation and Fundación Columbus to get off the ground. With these alliances in place, they eventually collaborated with the NIH. “Together, we applied for a grant and received $4 million from the state, which will fund a natural history study and, hopefully, a Phase I-III trial for our second program, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease 4J (CMT4J).”

Georgia Kumaritakis and Terry Pirovolakis pose for a photograph with their children Zach and Zoe, and their son Michael, who suffers from the rare neurodegenerative disease Spastic Paraplegia-50, at their home in Toronto.(Christopher Katsarov/The Globe and Mail)

FUNDING: THE BARRIER TO RARE DISEASE TREATMENTS

To any family, $4 million is an unfathomable amount of money. For Terry and Georgia, being able to see Michael enjoy life, ride his bike, play at the park, and understand affection was worth every cent, every hour, and every bump in the road. When funds were short, or the goal felt so far away, it was the people around them that helped them persevere.

“We thought we were going to have to sell our house at one point, but a generous mentor stepped in and offered to donate the $1 million we needed, allowing us to keep a roof over our children’s heads,” Terry says. People in the community stepped up to put on raffles, lemonade stands, galas, and other fundraisers. Raising funding to create these gene therapies is one of the biggest hurdles, and that’s exactly what Elpida Therapeutics hopes to tackle for other families impacted by rare diseases.

Up until this point, Elpida has relied on philanthropy to fund its work, but in the future, Terry hopes to leverage the Priority Review Voucher program through the FDA to take on more therapies and save more children. “This has never been about the money for me; it has always been about the children,” he says.

As Terry grows Elpida Therapeutics and continues working toward a world free of rare diseases, his focus will always be on the children and their families. When he looks into the eyes of parents or loved ones of those impacted by rare diseases, he sees himself and his own family, and he’ll fight for those children just like he fought for Michael.

“I feel incredibly blessed, humbled, and grateful that our community united to help us raise millions, with 13,000 people from around the world answering our call to support Michael and other children. It took hundreds of remarkable individuals to bring this therapy to these children, and we will be forever thankful for this extraordinary support.”