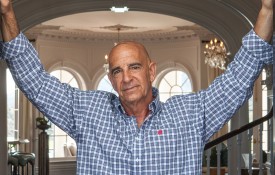

Robin Richards, CEO, chairman, and co-founder of CareerArc, has spent the last several decades as an onward-looking entrepreneur, seeking out underserved needs, uncovering unnoticed opportunities, finding the right matches between markets and the masses, and showing those who’ve worked under and alongside him how to do the same.

The Detroit-born son of a newspaper printing-press worker, Richards was borrowing and hustling his way into a coin-op video game business that operated 1,600 machines while he was still in law school. Soon he was using similar skills to launch Lexi International in the 1980s for next to nothing, turning it into the largest B2B tele-services and database management company in the United States by mid-1991 and eventually selling it to a private equity buyer for $34M.

That was the beginning of a pattern he’d repeat many times as his career synced with the commercial arrival of the internet. He leaned hard into the tech upheaval of entertainment through tickets.com and mp3.com, forever changed the way public institutions send essential notifications to the people they serve through the NTI Group Inc. (now Blackboard Connect), and democratized the paths into first jobs and next jobs via interships.com and CareerArc.

At the Burbank offices of CareerArc, he told us about his motivations and innovations.

You’ve clearly had a career-long hunger for the next big or interesting or necessary thing. Is this because you feel the urge to do something new and go find it, or because you see a need and decide to fill it?

I believe that technology, the internet in the beginning, the social networks later on, all of these things created massive opportunities where you could look at an industry and say, “If we did that right and brought it into this world, we could be more efficient in how we serve clients and impact both the top and the bottom line.” There are two ways to enter an industry. Create demand or follow demand. When you follow demand, you must have a better mousetrap. Lexi International, named after my daughter, started the year she was born, was my first real business. I had been a sales professional, and we spent 40 percent of our time filling out our calendar to go talk to people about the product that we were selling. And so I said, “What if I could teach somebody else to do that and I could find more selling time, which meant more revenue?” So I started out with that business creating an automated approach to appointment-setting for sales. I knew that the demand would be gigantic for salespeople because the one thing they hated to do was prospect. And I found out selling appointments was significantly more profitable than selling whatever product I could sell. Fast-forward 20 or 30 years, what do you have? SDRs in every single company.

Your own career arc seems like it has moved increasingly toward models of public service, whether it’s the mass notification systems of the NTI Group, the starter-job opportunities of internships.com, or the expansion of outplacement for workers at CareerArc. Has that been a conscious choice?

I wish I could say that what I’m doing things for is the public good. That’s nice to have, and something I’m proud of. But if I said it was the reason, I’d be lying. There is a lot of opportunity in delivering product and service to those that haven’t been lucky enough or haven’t been far enough up the food chain to get the product and service. We always ask, by doing this are we democratizing this service? With tickets.com, nobody could get a ticket that didn’t have a bunch of dough or have the ability to take time off work to go stand in line during the middle of the day at Tower Records. But as soon as there’s a computer, you can buy it online. So that turned out to be democratization. Internships.com was 100 percent, “There’s got to be a way for somebody that doesn’t have a fancy mom or dad or uncle to compete in the world of internships. There has got to be a marketplace built.” We built it and they came. Man, they came 100 miles an hour. So I don’t know. Is that always in the back of my mind? Or is it just a coincidence of 30 years?

How did your early life growing up in a blue-collar family in Detroit inform the businessman you became?

It was a modest upbringing with a lot of really smart people around me. And you start asking yourself, “What’s the difference in what the folks that have everything and us that are always scraping? Can I isolate the difference?” The people in nice cars, who went on vacations, either owned their own business or were doctors or lawyers. And I said, “Well, I don’t like school enough to be a doctor or a lawyer, so I’d better own my own business. The best way to do that is to probably get out of this environment.” So, I graduated from Michigan State and gave my mom and dad a hug. And I headed out the backdoor to as far away as I could go, which was California, and I’ve been here ever since.

You’ve been a mentor to many who went on to become major players in the technology and business community in Los Angeles, Silicon Valley, and beyond. How do you decide who would make a good protege?

I think mentoring is a great responsibility. So, you can’t do a lot of it, because you have to divorce yourself from the success being the reason. It’s really about development of the person and what they’re after. Because if you’re not careful, you start to judge the person’s value based on the company’s outcomes. So, you’ve got to be very careful to find people with the right integrity and the right work ethic and the right mindset and skill set and are hungry to be entrepreneurs. This person wants it bad and they believe they can do it right. Being a mentor is something you give because the person receiving it will use it wisely.

Can you talk about the Chase Foundation, the charity you started in 1992 to honor your son who died of cancer as a 2-year-old?

When you have a tragedy close to you, I think one of the things that helps someone get over that is the process of giving in their name. And that’s what we do with the Chase Foundation. My son died, and we got help with psychosocial services for my surviving daughters. It was incredibly helpful. And a terrible time. I sat there at the hospital while he was dying, and there was another couple of dads who sat there, too. One didn’t speak any English. The other guy was a tough blue-collar guy. And the only guy that got the services was me. Didn’t seem fair. So, as a family, we kind of decided to eradicate that problem as much as possible over our lifetime. Let’s convince hospitals that you need a playroom that is a no-doctor zone, and psychosocial services for the kids that are in there. Now, have we eradicated it? No. But I’ll bet you in L.A. County, we’ve overcome 50 percent of the problem.

And would those two other dads have the same services as you today?

If they were in L.A. County today in any of the hospitals we do business with, they’d have psychosocial services free of charge. One hundred percent.